15/06/2022

Il (Meta)Cinema Ritrovato

The “cinephiles’ paradise” is a space-time bubble where one can enjoy the wonders and the thousand faces of cinema, from the aesthetic to the socio-cultural, to the technical. At the same time, a place to discover those (not so) rare cases in which cinema reveals its secrets and places them at the centre of the scene. When cinema takes a moment to reflect on itself, to play with its characteristics and limitations.

Below we have compiled a short list of vision tips, referencing this year’s festival program, in which a metalinguistic intention of cinema becomes evident:

- Tools of the trade: cinema seen from within

From the section “One hundred years ago: 1922”, Secrets of a World Industry – The Making of Cinematograph Film (United Kingdom/1922), “shows the manufacture of film, including perforating, developing, drying, printing, grading, cutting and packing. It is a very rare look inside a film laboratory of the 1920s giving us a glimpse of the machines, people and processes that went into making and delivering the film prints to the film companies.” (Bryony Dixon and Karl Wratschko). - In a black and white world, clothes can only be grey… or maybe not!

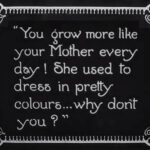

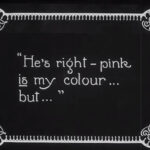

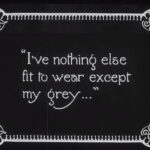

From the section “One hundred years ago: 1922”, the advertising film Changing Hues, “a dramatised advertising film, in which a girl who cannot afford a new dress transforms her old one with Twink dye. It begins with her artist lover asking why she is always in grey or white. She looks at herself in a mirror and examines her wardrobe. Finding nothing to wear but grey, she and her younger brother and sister go shopping, and come across a shop window displaying Twink Dye and Sunlight Soap, both products of Lever Brothers. She follows the instructions and dyes a grey dress a bright pink. The final scenes see her dancing with the children to an old Scottish tune Comin’ Thro’ the Rye. The film is hand-and-stencil-coloured with some multi-coloured sections in what were called ‘jazz tints’, which fluctuated from one colour to the other” (Bryony Dixon). - The mirror screen: let’s talk about you

From the section “Rediscovered and Restored“, I figli di Sansonia by Filippo Costamagna (Italy/1920). A message becomes clear halfway through the film: “News from father I’ll be back in a few days. The film is almost finished. Here are some scenes that you can complete in your screening room”. At that point one looks down to see film strips (with great pleasure!), “Now we will project the scenes!”. And this is how the mother and the two children meet in the villa’s projection room to enjoy the magic of cinema: mise en abyme, a screen within the screen. - When metacommunication is sung, danced and worshipped

From the section “Rediscovered and Restored“, Singin’ in the Rain by Stanley Donen and Gene Kelly (USA/1952). The red carpet, the stars, the delirious audience, the paparazzi, the (silent) black and white screen in a colour room, and the studio set (lighting of skies, artificial wind, and atmospheric smoke) as a strategy of courtship, the challenges of sound, the dubbing room. In Singin’ in the Rain there is all of cinema in the background! “Singin’ in the Rain is therefore a nostalgic film, the revisiting of a past that is perhaps not too distant in time, but is light years away in terms of taste, mentality,fashion and, naturally, technology.

So distant that the opening sequence, with its long shot from above of the Grauman’s Chinese Theatre, has the feel of a scene lifted from an animated cartoon: the colours, the lights, the distant movements, the architectural lines don’t seem at all real (recreated), but instead seem to belong to a different imaginary order – that of a reality transfigured by a childish and infantile fantasy, sparkling and microscopically great” (Franco La Polla, Stanley Donen, Gene Kelly. Cantando sotto la pioggia, Lindau, Turin 1997). - Films within films: Part 1

From the section “Documents e Documentaries“, Et j’aime à la fureur by André Bonzel (France/2021) “who relives his life through the mini-films of others and affirms that “All our past is perfectly conserved; we are a suite that repeats itself; I am nothing more than a link in a repeating chain”.

“Telling one’s own story through the images of others is a nice idea, at once modest and generous, entailing all that film – and only film – can produce in terms of shared experience… A name, Bonzel, that may be known to cinephiles is someone who, in 1992, together with Rémy Belvaux and Benoît Poelvoorde, put his name to C’est arrivé près de chez vous, a prickling Belgian reality-TV satire about a serial killer. Bonzel was the French camera-man in this unholy trinity, who joined forces while they were at INSAS, the famous Brussels film school. From what we know, a strangely unfortunate fate ensued for actor Benoît Poelvoorde and more tragically for Rémy Belvaux, who took his own life in 2006 after embarking on a career in publicity film production; Bonzel disappeared from view. At 60, he reappeared with this montage film, a gem of sensibility and emotion…” (Jacques Mandelbaum, Et j’aime à la fureur: journal intime sur pellicules anonymes, “Le Monde”, 20 April 2022). - Films within films: Part 2

Among this year’s Documentaries during Cinema Ritrovato is another re-edited film: Her Violet Kiss by Bill Morrison (USA/2021). The film “re-contextualises a scene from a lost silent German title Liebeshölle, 1928 (or Pawns of Passion, 1929) for contemporary audiences during a global pandemic.

The source film was directed by Wiktor Biegański and Carmine Gallone, and stars Olga Tschechowa. It was believed to be a lost film until Bruce Lawton uncovered an incomplete print in a cache of films that had been stored in a barn in Pennsylvania and donated it to the Library of Congress National Audio-Visual Conservation Center. Director Bill Morrison scanned the print in 2013, and this copy had remained in his personal archive, unseen until now. In this revision, the deteriorating nitrate print has been scanned, slowed down, and re-edited with Michael Montes’ score”. - The metaphor for the end of a cinema and a generation

From the section “Rediscovered and Restored“, The Last Picture Show by Peter Bogdanovich (USA/1971). A group of teenagers graduates from high school in the bleak Texas town of Anarene. With the end of adolescence comes the flat (violent) reality of adulthood. The last screening (Red River by Howard Hawks) closes forever not only the town’s cinema but also the illusions of an entire generation who find themselves at the gates of the Korean war, which will take away the lives of many young Americans. “A cinema of nostalgia? Not in the (often sterile) sense that could be applied to other films of the period (including those of the same filmmaker). As Franco La Polla wrote in Il nuovo cinema americano 1967-1976, through his hyperrealism, Bogdanovich “recreates reality;he represents it in a way that does not deny the act of fabrication, but rather emphasises it as such. In The Last Picture Show,Bogdanovich’s cinema ceases to be fiction, the attempt to piece together bits of an artificial reality; rather, it becomes the reinterpretation of the basis of that false reality through its reutilisation with a complete awareness of its fabricated nature. The Last Picture Show is probably the only contemporary American film, at least among ‘regular’ film production, in which the hyperreal component is fully theorised.” Therefore,that which at first glance can appear nostalgic or reassuring soon reveals itself to be a heartrending journey into the imaginary, mythological falsification of classical cinema and into the senseless, depressing reality that (now as then) underpinned that representation. This is why TheLast Picture Show is so sad, because the myth (although beloved) reveals the fragility and mutability of its foundations, be they cinematic or the stuff of dreams and memories”. (Emanuela Martini, Shall We Gather at the River? Tra il West e il nulla: L’ultimo spettacolo, “Cineforum. Nuova serie”, n. 5, March 2022).