Photography and cinema (and their liaison dangereuse at Il Cinema Ritrovato)

Making movies you’re not trying to capture reality; you’re trying to capture a photograph of reality.

Stanley Kubrik

In the program of the 36th edition of Il Cinema Ritrovato, across the sections, we can identify a common thread dedicated to photography: on the one hand, we propose films involving great names of the photographic art; on the other hand, we point out in this article some titles that have become famous for the care or the uniqueness in the choices of the direction of photography.

***

Two films dedicated to the works and the artistic activity of two photographers (and not only) that have changed the history of photography and cinema as we know them today:

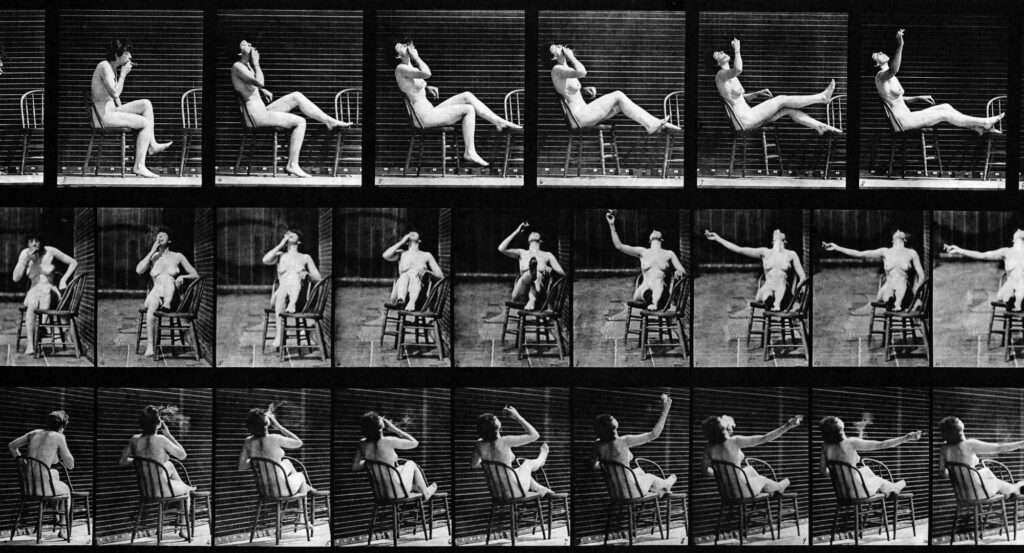

Exposing Muybridge (Marc Shaffer, 2021) in Documents and Documentaries

The best way to talk about the film and its protagonist is through the words of its author Marc Shaffer: “As I learned more about the complicated photographer, the first to capture with a camera something moving faster than the human eye can see (those galloping horses), I became seduced not only by his images but by his extraordinary story, one that dripped with melodrama and read like a prequel to our own. […] As I dug deeper, I watched as Muybridge wielded his camera to produce fact and fiction, document and distort, make myth and tell stories, and if you look hard enough, reveal a kind of truth, if not always what it appeared to be at first glance. In that process, I saw myself as a descendant of this man, standing behind my camera, searching for my truth, as I created my version of Muybridge for you to see”.

The Treasure of His Youth: The Photographs of Paolo di Paolo (Bruce Weber, 2021) in Documents and Documentaries

A film by a great photographer, Bruce Weber, about another great, recently ‘rediscovered’ photographer, Paolo Di Paolo.

“About 20 years ago, I was in the basement of my parents’ house searching for my skis. As I was looking around, I discovered a filing cabinet stuffed with negatives and orange Agfa boxes filled with prints. I asked my father, “What are these pictures?” He said, “Well, I was a photographer once.” I was 20 years old at the time, and he had never once mentioned this to me. I had always known my father as a writer and historian – that had been his profession all my life. […]

My father always used natural light and favoured spontaneity over a carefully constructed image. He considered himself an amateur – taking photographs out of love and passion – who was fortunate that it became his profession” (Silvia Di Paolo).

“Paolo’s photographs have touched my soul – they are like lines from the golden age of Roman poetry, or an aria sung by Franco Corelli. I’m excited to see him join the ranks of renowned photographers of his time, including Cartier-Bresson in France or Cecil Beaton in England” (Bruce Weber).

Paolo di Paolo e Bruce Weber, friends and photographer, will introduce the film together on june 28th at 6:30 p.m. at MAST (reservation is required at www.mast.org).

***

Alongside these two examples, expressly dedicated to the art of capturing reality in still images and making it eternal, there will be many films of the Festival characterized by a direction of photography that has made people talk about itself and that amazes for its narrative, aesthetic, semantic, and/or technological values:

Nostalghia (Andrej Tarkovskij, 1983) in Recovered and Restored

Thanks to the work of CSC – Cineteca Nazionale and a complex restoration, we will present Andrej Tarkovskij‘s penultimate film, a poem about homesickness and faith, the director’s farewell to his homeland and a celebration of madness, in which he and Beppe Lanci – who also followed and curated the restoration – invented a poetic style of cinematography that had never been used before, alternating black and white, colour and halftones between the two.

Geometric framing, gazes into the camera, a soundtrack filled with singing, dripping, barking, and images continually flooded with rain, snow, thermal baths and puddles – sometimes in black-and-white and other times in colour or half-tones.

It will be possible to find out much more about this difficult and exciting restoration during a specially dedicated meeting: Case Study: Restoring Andrej Tarkovskij’ Nostalghia with Alberto Anile (CSC – Cineteca Nazionale), Giuseppe Lanci (cinematographer).

Una giornata particolare (Ettore Scola, 1977) in Forever Sophia

In order to evoke the atmosphere of an oppressive past, the director and the cinematographer Pasqualino De Santis undertake a highly radical and visually experimental project. Scola wrote: “Right from the start, the entire setting and all items of clothing were stripped of colour. Then we shot with a special filter, and then the colours were muted again during printing. And this was not only to make the photography look more like the snippets of documentary that I had opened the film with, but also because my memories of the house in Piazza Vittorio where I lived at that time are in those tones. As I recall it, the colour of Rome in those days was a non-colour, not even grey but a bit cloudy, a bit dense, like a fog inside the rooms, which in the film was a kind of symbol – even if I’m not a huge fan of symbolism – of closure, of prison, of exclusion.” Technicolor developed a printing process – ENR – that desaturated the colours to obtain the photographic tone Ettore Scola and De Santis wanted. The process is no longer reproducible on film, and recreating it was only possible thanks to digital technology. The work of the CSC – Cineteca Nazionale was carried out at L’Immagine Ritrovata laboratory under the supervision of Luciano Tovoli and Ettore Scola himself. It won the Golden Lion for the best restored film as part of the Venice Classics 2014.

Et j’aime à la fureur (André Bonzel, 2021) in Documents and Documentaries

Telling one’s own story through the images of others is a nice idea, at once modest and generous, entailing all that film – and only film – can produce in terms of shared experience… A name, Bonzel, that may be known to cinephiles is someone who, in 1992, together with Rémy Belvaux and Benoît Poelvoorde, put his name to C’est arrivé près de chez vous, a prickling Belgian reality- TV satire about a serial killer. Bonzel was the French cameraman in this unholy trinity, who joined forces while they were at INSAS, the famous Brussels film school. At 60, he reappeared with this montage film, a gem of sensibility and emotion… As Bonzel explains in the introduction to the film, which he himself narrates, he used family movies that he had been collecting all his life. In the images provided by dozens of anonymous amateurs showing good-natured, happy family photos, captured on celluloid and incorruptible, there emerges a personal story, more sombre, more fragmented, more mysterious; we soon understand the justification for resorting to the filmed happiness of others in the writing of that story.

Il Carso (Franco Giraldi, 1960) in Documents and Documentaries

A short produced by Documento Film and shot in the Carso region near Trieste during the Christmas holidays of 1959. Its director believed it lost until three years ago. Franco Giraldi, at the time a former film journalist who had moved to Rome and was working as an assistant director, produced an extremely personal, bittersweet ‘western’ fresco about his homeland. Through indelible images, Giuseppe Pinori – later a cinematographer for Nanni Moretti, Marco Tullio Giordana and the Taviani brothers – immortalised the hard, daily work of the fisherman and peasants of Santa Croce/Sveti Križ.

Ken (Kenji Misumi, 1964) in Kenji Misumi: an instinctive auteur

Misumi worked almost exclusively with period material. This was a rare gendai-geki (film with a contemporary setting), atypical in that and, by comparison with Misumi’s other films of this period, in its austere black-and-white ‘Scope photography (cinematographer Chikashi Makiura was also responsible for the glowing colours of Kenki, among other collaborations with Misumi).

Až přijde kocour (Vojtěch Jasný, 1963) in Recovered and Restored

Až přijde kocour was Jasný’s first widescreen colour film. He used colour not in order to create a mechanical imitation of reality, but to endow reality with new meaning and amplify the statement of the whole work. The very genre of the film encouraged such a treatment – a modern fairytale with components of satire and parable. The key ‘character’ is a magical cat, whose gaze causes people to change colour

according to their attributes and actions. Liars become violet, thieves are grey, unfaithful people are yellow and those in love become red. At the time of the film’s original release, both general audiences and professionals assumed the colorization was produced through laboratory processing. But that was only partially true. The perfection of the trick was achieved through the actors’ clothing and masking as well as Jaroslav Kučera’s camerawork. His artistry is also visible in less spectacular scenes, where he underlines the beauty of the Czech countryside and the photogenic grace of the town of Telč.

The Godfather (Francis Ford Coppola, 1972) in Recovered and Restored

Surprisingly, two of Coppola’s key creative choices, which now seem indispensable to both this and the subsequent films of the trilogy, were initially contested by Paramount. Director of photography Gordon Willis perfected his low-key lighting register and extensive use of shadows, subtly injecting sepia into the colour balance, and helping establish a new era in cinematography. And for the composer Nino Rota, who had worked with all the great postwar Italian filmmakers, but never on an American film, The Godfather would bring lasting worldwide fame.

Carmen (Francesco Rosi, 1984) in Recovered and Restored

Having overcome an initial reticence due to his lack of familiarity with opera, Rosi soon became passionate about the project – “I believe that Carmen is the most cinematic of operas” – and discovered that he was in agreement with Bizet who “viewed the love between a man and a woman exactly as I do: the love between two beings who are, and who inexorably remain, adversaries”. He wanted to produce “a visual interpretation, not only of the libretto, but also of the music”, so that “every note found its equivalent in a precise image which would make an impact on the spectator” thanks to the plasticity and chromaticism of Pasqualino De Santis’ cinematography.

Tenebre (Dario Argento, 1982) in Recovered and Restored

“Tenebre signals a break from my previous two films [Suspiria and Inferno]. Bright colours have been replaced by photography that is virtually black and white. Eccentrically blended set designs have been replaced by a never-seen-before Rome, slightly futuristic, with little traffic, a bit of green, and beautiful houses inhabited by unbalanced people. I shot it in the EUR district, but I also made use of beautiful, original interiors like the architect Sandro Petti’s villa, where there are walls full of splendid collages by the painter Mimmo Rotella. I even tried to illuminate the nighttime murders, as if they took place in the light of day. I wanted to demonstrate that shadows are not murder and horror’s only companions – so, too, is the daytime. Darkness=fear is an obsolete formula” (Dario Argento, in Fabio Maiello, Dario Argento, confessioni di un maestro, Alacran edizioni, Milano 2007).

Decameron Nights (Hugo Fregonese, 1953) in The drifter’s escape: Hugo Fregonese

Decameron Nights is a handsome, confident film, cleverly structured to show off both its Spanish locations (mostly doubling for the Florentine hills) and the considerable gifts of its cast. Again we find Fregonese’s familiar themes of imprisonment and escape, here transposed to the erotic realm. Working with British cinematographer Guy Green, Fregonese subtly manipulates the color palette, contrasting the natural lighting and earth tones of the framing story to the expressionistic shadows and bold, primary colors of the imaginary tales. This is a lush and generous film that stands as a delightful contrast to Fregonese’s darker works.

Black Tuesday (Hugo Fregonese, 1954) in The drifter’s escape: Hugo Fregonese

This ferocious film noir proved to be Fregonese’s last Hollywood film. Cinematographer Stanley Cortez, shooting the first feature film on Kodak’s revolutionary high-speed black-andwhite Tri-X stock, contributes images that rival the spatial complexity and prickly detail of his work on The Magnificent Ambersons, while looking forward to the strong, nearly abstract use of negative space that characterizes his contributions to The Night of the Hunter (a film with which Black Tuesday shares a mysterious family resemblance).