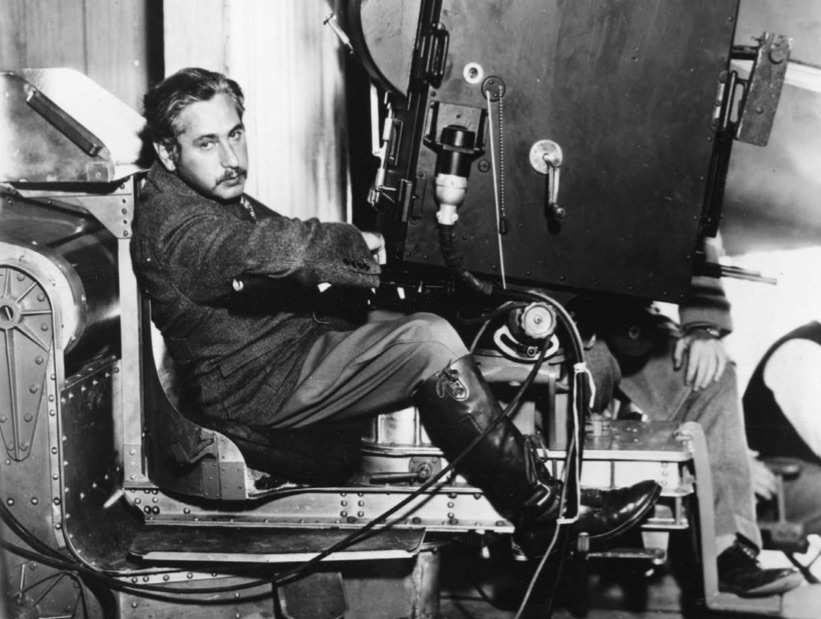

JOSEF VON STERNBERG, NOT ONLY DIETRICH

“I preferred an unclarity that might lead to an accidental greatness to a clarity that could at best result in something mediocre.”

Josef von Sternberg, Fun in a Chinese Laundry

Our tribute to the great master of light and sound in the service of abstraction (or is it eroticism?) is composed of two sections of screenings and three special dossiers. The first series of screenings is devoted to Sternberg’s neglected early period “Sternberg Before Dietrich”, beginning with his first film, The Salvation Hunters (a new preservation from UCLA Film and Television Archive)through his first sound film Thunderbolt. The second series gives us the American Sternberg-Dietrich era, itself not nearly well- enough appreciated. We include in the first group the rarely-seen Children of Divorce, directed by Frank Lloyd then half re-shot and edited by Sternberg, and do not define the second by Dietrich alone, omitting The Blue Angel and including the under-rated An American Tragedy.

We are fortunate to have the director’s son, Nicholas von Sternberg, as our guest for the entire festival. He will be on hand to introduce the Sternberg screenings and will play a featured role in two of the special dossiers.

The dossiers are meant to bring us closer to the world of Sternberg’s career and to his unique vision of the cinema. Among the highlights: Nicholas von Sternberg, a career cinematographer, will discuss visual design in his father’s films, his father as he knew him and as he was told about him later by professionals who had worked with him. We include two precious filmed interviews with the director (Cinéastes de notre temps, “D’un silence l’autre – Paris 1966; The World of Josef von Sternberg, with Kevin Brownlow, London 1967), and home movies with Marlene Dietrich, Paramount’s promotional film with fashion fantasy king Travis Banton, The Fashion Side of Hollywood, another chance to see the rediscovered fragment from Sternberg’s lost 1929 The Case of Lena Smith, a look at Sternberg’s career from The Salvation Hunters to his first commercial success Underworld, and a session on Sternberg’s lost 1926 Sea Gull / Woman of the Sea, which was produced and then refused release by Chaplin.

Nothing is more certain than that Sternberg’s films cannot be appreciated – not really – unless they are projected onto the big screen. And the experience is most intense if they are seen in a concentrated period of time. If words cannot describe them, neither can the small screen. Sternberg’s films need to be BIG because the first shot already moves you toward an unexpected, imaginary world built up through detail, with orchestrated light and shadow, movements in and out of visibility, something in the way or revealed only for a moment, making you want to see more. On the small screen, essential details vanish into obscurity, even on recent DVDs (see The Scarlet Empress, where Sternberg’s long, long superimpositions sink into muddy half-darkness). To salute the magical light of Josef von Sternberg, Il Cinema Ritrovato brings you the best 35mm prints known to exist.

At the end of 1931 after seeing An American Tragedy, French critic André-R. Maugé observed: “The films of Josef von Sternberg are shown around the world. People argue about them and often criticize them for being too personal, too full of his own obsessions to appeal to the general public. But everyone notices those beautiful women living through the most tragic and emotional moments of their imaginary existence. Distant and tired, they lounge on divans, a cigarette in their fingers, crossing their beautiful legs high, their faces showing that there is no hope for love. Everyone sighs: “What a wonderful actress!” without realizing that it is Sternberg, through them, who strikes these nonchalant poses, that he is the one speaking with their soft, veiled voice, that his look is filtered through their half-closed eyelids. Still, we can’t stop remembering these passionate creatures around whom love never stops intruding, dying and being reborn. Josef von Sternberg, one of the rare men in the cinema who really has something to express and who does it the way he wants to, without worrying about what will happen later.”

Janet Bergstrom