The Keaton Project 2015

Programme curated by Cecilia Cenciarelli

On September 1949, “Life” magazine published James Agee’s possibly most famous piece called Comedy’s Greatest Era. Situated somewhere between journalistic inquest and poetic account, Agee’s celebration of four masters of silent comedy – Lloyd, Langdon, Keaton and Chaplin – aimed at reminding America of the uniqueness of an art form that was already slipping into oblivion.

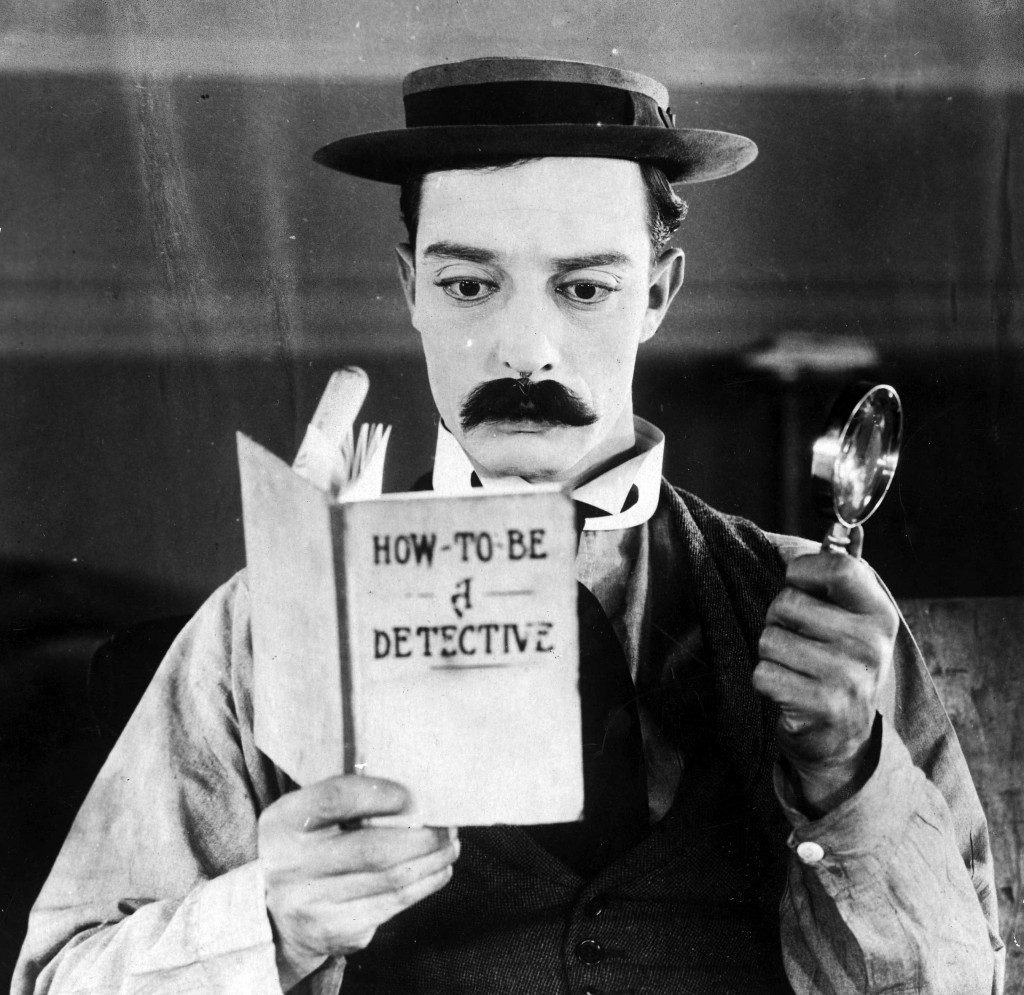

In particular his portrait of Buster Keaton beautifully captured the essence of his art and marked the first critical appreciation that Keaton enjoyed since the end of his golden age: “He was by his whole style and nature so much the most deeply ‘silent’ of the silent comedians that even a smile was as deafeningly out of key as a yell. In a way his pictures are like a transcendent juggling act in which it seems that the whole universe is in exquisite fly- ing motion and the one point of repose is the juggler’s effortless, uninterested face”. Agee’s influential piece triggered a process of artistic rehabilitation and contributed to a new interest in Keaton’s masterpieces, at the time virtually unavailable.

At the beginning of the 1950s, thanks to his partnership with Raymond Rohauer, Keaton’s films were re-released. Although Keaton did not own the rights to his film, much to his frustra- tion, he had kept some rare prints, later transferred to safety stock. Several other ‘lost’ films were found by James Mason who had bought Keaton’s Italian Villa.

Like many collectors and distributors of the time, Rohauer would often alter the film’s editing or replace the original cards to claim copyright on them, charge a licensing fee and, one might argue today, make restorers’ life ‘more interesting’. As we embark on the challenging restoration of Keaton’s 1920-1928 short and long features, we know for a fact that studying and comparing the great wealth of the existing elements will be as time-consuming that the actual restoration work.

We owe a great debt to film historians and maverick restorers – Kevin Brownlow to name but one – who have paved our way and reminded us that restoration is not just about technical virtuosity but must necessarily involve a deep under- standing of cinema and its inner dynamics. Keaton’s films are, arguably, one of the most extraordinary exploration of film as a self-defining object, or, in Walter Kerr’s words: “While others, like Chaplin, were using film to point at themselves, Keaton pointed in the opposite direction: at the thing itself. He insisted that film was film, he insisted that silent film was silent. Whatever was idiosyncratic about him – clothes, stance, emotional makeup – would have to find expression in and about these two prime facts”.

Cecilia Cenciarelli