The Invention of Love

I first came across the poem A Invenção do Amor one autumn day in 2002, in Lisbon. I had been living there for a few months, and I had studied Portuguese, but this was the first time that the written word in this foreign language had suddenly come to life, writhing as though trying to escape from the page.

Go out, run, sing! I felt a strange urgency to declare the poem to everybody, to set it free from my room and take it around the streets, to show it to strangers. So I decided to make leaflets with excerpts from the poem and then went out at night to put them up around the streets. For a few months I was doing as many as 35 a week. At the bottom, where advertisement posters usually have phone numbers that people can tear off, I put words from the poem on little strips, so that people could take the words with them. It was important for me that those words should spread like seeds among the people. I didn’t want them to just be ‘page words’, but rather messages to be taken, exchanged, rolled up, stuck on to things.

It’s now 2020, and the poem still retains the same power. Daniel Filipe, a Cabo Verdean poet persecuted by the Salazar regime, never knew that his words would go on to become one of the songs of the Portuguese revolution in 1974. He died at the age of just 38, and didn’t live to see the overthrow of the dictator and the liberation of 25 April.

During the lockdown for the pandemic, his words came back to me. I looked for them and eventually found them. I called Mara Cerri, Fausta Orecchio, Luciana Fina and my friends at Else Edizioni. I wanted to translate those words, illustrate them, print them and make a poster-book out of them, to spread the love of Daniel Filipe!

And so we discovered that these words are still able to tell the vivid story of an epidemic that in certain ways is the opposite of the one we’re currently experiencing. An epidemic of hope, like a flow- er blossoming in our memory. For the time that is to come.

Alice Rohrwacher

March 2020, a dystopic time when it was decreed that people must keep an unprecedented distance from each other. And yet, at that very moment, an inven- tion managed to let a breath pass anew between distant times and places.

Alice called me from Italy while I was dealing with the difficult forced isolation in Alentejo, near Grândola. She was looking for an original edition of A Invenção do Amor, the poem by Daniel Filipe, and she wanted me to translate it with her because she intended to prepare a series of posters for the 25 April cel- ebrations. That date marked important changes for both Portugal and Italy, 30 years apart. And so those verses became a part of my daily life, before finally taking flight and bridging time and distance. On 25 April, the words of the poem were displayed on posters and billboards in many Italian cities, accompanied by illustrations by Mara Cerri. Then it was decided to print a book featuring the text and posters through Else Edizioni, with the help of Marco Carsetti, Chiara Mammarella and Fausta Orecchio.

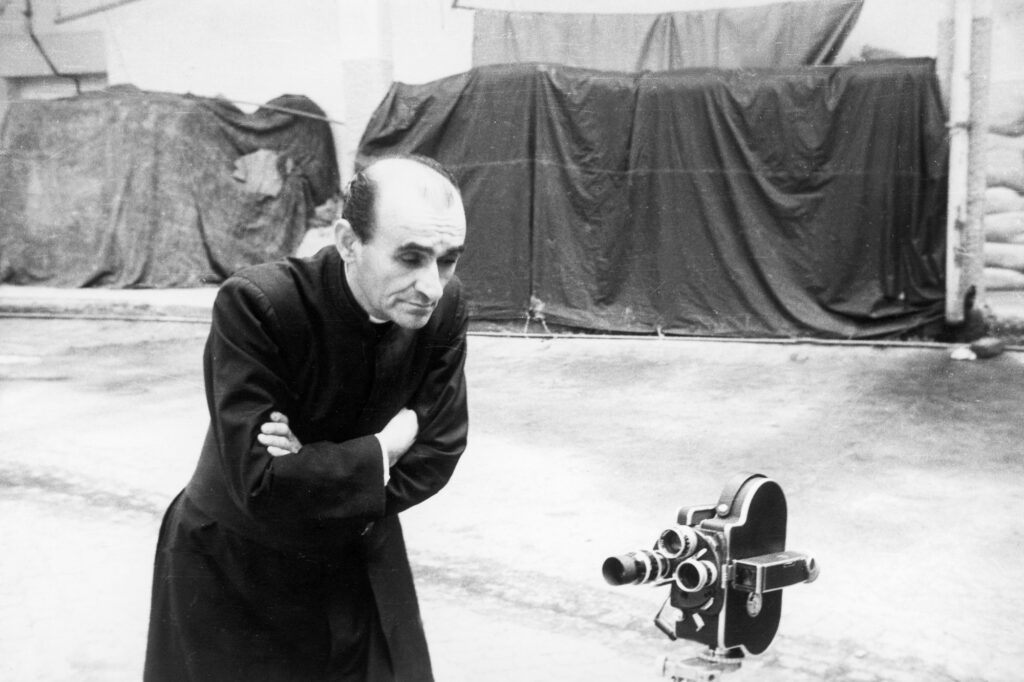

We also enjoyed watching the film directed by António Campos in 1965, just four years after the poem had been written. Portugal at that time was still ruled by the Estado Novo regime and under the strict control of the PIDE. Campos was a small-town filmmaker, largely unknown, a solitary and romantic figure. He chose to work by his own means, out- side the system and the times, preferring 8mm or 16mm film: hard work that went unrewarded. He was one of the first cult figures of Portuguese documentary-making, and was appreciated by Cinema Novo directors for his unorthodox style and his independence. His film was a free and visionary creation and was itself, in a certain sense, an invention of the opposite of what we’re experiencing in our times.

Since 1961, Filipe’s poem has fuelled dreams of love and revolution for generations of Portuguese people. It was adapted for the cinema by António Campos, recorded on vinyl with the poet’s own voice, and performed in theatres many times. Even today it spawns new initiatives, letting us dream again. Thanks to Alice and the contributions of Mara, Marco, Chiara and Fausta, thanks to Ernesto Rodrigues and Marcelo Felix in Lisbon, who helped me in my search for the original edition of the poem and a copy of the film, thanks to Cinemateca Portuguesa, to Gian Luca Farinelli, to the festival and to the audience, the invention has been found once more.

Luciana Fina