Itinerant Cinema Ritrovato. Treasures from Théâtre Morieux Collection

An Exhibition in Sala Borsa (June 18th – August 31st)

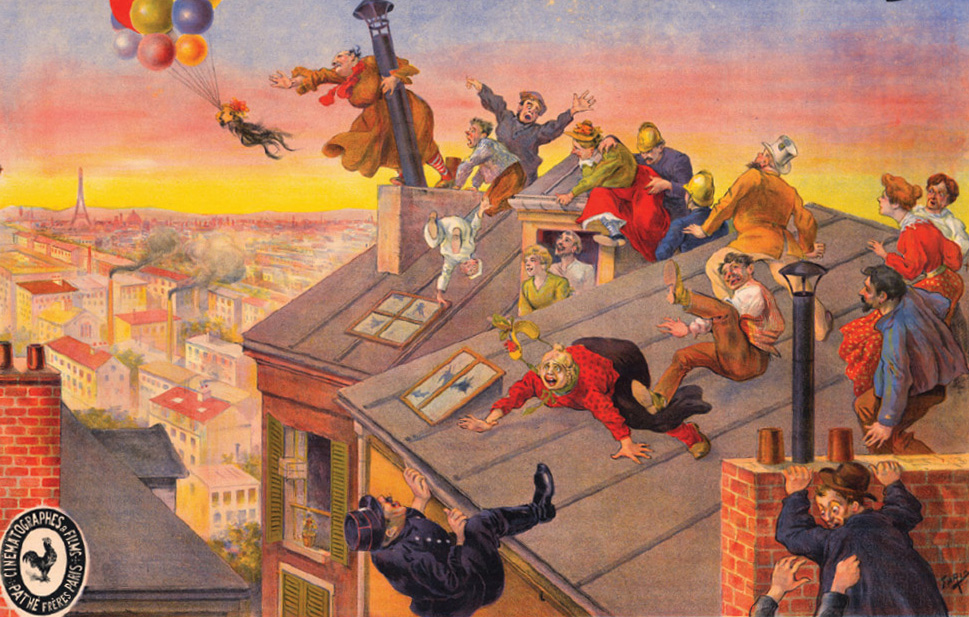

The exhibition Itinerant Cinema Ritrovato. Treasures from Théâtre Morieux Collection shows magnificent posters and photographs from the collections of Fondation Jérôme Seydoux-Pathé and Musée Gaumont, as well as original components, never shown before, of a facade of the Théâtre Morieux, now property, together with dioramas and thousands of mechanical puppets, of Jean-Paul Favand’s Musée des Arts Forains in Paris.

We want to thank Assessorato alla Cultura di Bologna, Manuela Padoan, Sophie Seydoux, Stéphanie Salmon, Corine Faugeron, Agnès Bertola, Jean-Paul Favand, Dominique Hebert and Béatrice Lassus, whose generous help made this exhibition possible

Finding Morieux

There are dreams that the conservators do not dare to dream, such as finding in a single source a hundred or so films dating from 1902 to 1909, many of them unique prints, together with projectors in their original wooden boxes and hundreds of original posters from 1903 to 1908, the colours looking fresh from the printers. Impossible as it may seem, that dream has become a reality. It all started in 2006 with a simple email from a person who said he was in possession of,Gaumont and Pathé cinematograph materials. He was in Belgium and had been charged with clearing a warehouse. It was during the clearance operation that he had discovered – beneath fifteen centimetres of dust – posters, films, projectors, as well as sets and puppets, which had been patiently waiting for 100 years. By consulting various archives and programmes, we discovered that these were some of the materials for shows at the Itinerant Théâtre Morieux, and that this was only a small part of the treasure.

(Manuela Padoan)

Morieux and Pathé

The Morieux Collection takes its name from a famous fairground show, a sophisticated mechanical theatre active in France and Belgium in the 19th century. It featured metal marionettes brought to life before moving panoramas. In 1888 or 1889, Morieux sold his business to the Belgian painter Léon Van de Voorde, who outdid rivals by presenting threehour spectacles of ever greater perfection, 44 ending with a magic lantern show. This was replaced in 1906 by moving images. From now on the Morieux posters would announce a Cinématographe Géant with the fancy name Impériator Bio. Van de Voorde used a Chrono ABR, Pathé’s most popular projector. We learn of the vagaries of its acquisition from the correspondence with Pathé’s French and Belgian offices: the projector was ordered in May 1906 and delivered in June, initially suffering technical problems. But for the Liège Fair in October everything was ready. Also at the Liège Fair was Willem F. Krüger’s “Imperial Bio – Grand Cinématographe” which had been showing Pathé films in Belgium since 1903. It is possible that Van de Voorde acquired one of his two booths from Krüger, a hypothesis based on documents in the collection. This booth was constructed by Alexandre Devos, from Gent. According to the advertisements, it had a 100 m² screen, was 35 metres long and could accommodate an audience of 600. Van de Voorde became a good customer of Pathé (buying Gaumont films too, but rather fewer). Of his 100 Pathé films, 88 were released between May 1906 and August 1907. It seems it became difficult for Van de Voorde to acquire prints after the creation, in February 1908, of Belge-Cinéma as Pathé’s franchiseholder for the distribution of their films in Belgium. He still bought some Pathé films in 1908 and 1909, among them L’Assommoir. But he also established a business relationship with Ambrosio and around 1916 started renting prints from the distribution companies Bruxelles Film Location, Jos Van Damme and Océanic Films. He also diversified into a live performance based on the Passion of Christ and remained faithful until the end of the 1920s to the tradition of the Morieux animated theatre.

(Stéphanie Salmon)

History of Cinema Is a History of Light

Il Cinema Ritrovato was once a festival at which audiences were introduced to films of the past in restorations on 35mm safety film – the same material as was then seen in ordinary cinemas. Today the festival shows (not only, but also) digital DCP versions, again just as in every cinema. In the digitised present, Il Cinema Ritrovato has clear responsibilities: it is becoming ever more important for audiences to encounter the materials and technologies of cinema’s past. The different emulsions, for example. The carbon arc light, for example, used in projectors before the intoduction of xenon lamps in 1956. The technical aspects of our two special screenings with carbon arc light have been organised by Stefano Bognar of Cineservice. But not only the projection is fulfilling the promise of rediscovering a cinéma perdu: all the films in these programmes are rediscoveries. They are from the find of the century, holdings of the Belgian Van de Voorde family which ran the legendary Grand Théâtre Mécanique, Pittoresque et Maritime Morieux de Paris from around 1885 to 1930

The Films. Pathé 1906-1907

It’s a miracle! In March 2009 beautiful prints of several lost Capellani films appeared on the Gaumont-Pathé Archives website. (I asked Manuela Padoan where they came from. From Belgium, she said, from a fairground show…). Capellani’s scènes dramatiques of 1906 these were great short films. But viewing more films from the Morieux collection, we realise that these were not exceptional – simply the norm, typical productions of the best years of Pathé. Of the 92 Pathé films, 67 of them from the years 1906-1907, most were great short films. (There are some long ones too, such as the grand 1903 Epopée napoléonienne, which we hope to show next year). These two programmes should give an indication of the insights the Morieux collection can provide. They are about the beauty of anonymous scènes dramatiques of 1906, about colour combinations in 1907, about fire and water, about death on screen, about children and music hall artists. Films full of wonders and discoveries.

Exhibition and Programme curated by Mariann Lewinsky