ANNA MAGNANI, THE ONE AND ONLY

Curated by Emiliano Morreale

Anna Magnani represented for the cinema something close to what Eleonora Duse had for the theatre. She was certainly a symbol of Italy, but also an emblem for the very profession of acting. The role of Pina in Roma città aperta was immediately replicated up until the mid-1950s in a myriad of lesser variants of the heroic or comic woman-of-the-people, from L’onorevole Angelina to Molti sogni per le strade. The symbolic pose of such roles is that of a woman in a crowd, restrained as she fights with anguish against historical injustice (Roma città aperta, Un uomo ritorna, L’onorevole Angelina…).

However, Anna Magnani was much more besides; before the war she was both a showgirl and serious theatre actress (as her earliest film appearances, Teresa Venerdì above all, testify) and after the war she took on such unexpected roles as in the monologue Una voce umana, which Rossellini filmed as part of L’amore, or in Renoir’s Le Carrosse d’or. She also managed to conquer Hollywood, performing in English, and becoming one of the few non-native speakers to win the Oscar for the Best Actress, for The Rose Tattoo in 1956. Although it was never equalled, her acting style influenced actresses around the world, from the Far East to those who came out of the Actors Studio. The persistence of some of her characteristic gestures, such as bringing her hands to her throat or breastbone or using the back of her hand to wipe her forehead, provide an unmistakable indicator of this influence (remember how Meryl Streep made use of these gestures, almost as if she were quoting Magnani, in The Bridges of Madison County).

“She-wolf and vestal virgin, aristocrat and tramp, brooding and clownish,” was Federico Fellini’s definition of Magnani as he followed her in Roma, a mini-cameo which only lasts a few minutes and was destined to be her final appearance in the cinema. It is safe to say that such an actress could not exist today. But Magnani was unique and a maverick even then. Confounding on the stage, including in her audition for the Academy of Dramatic Arts, and disconcerting as a star, she was often criticised or mocked in the mainstream media – too big for our cinema and as symbol for a lost Italy, “the face of a past which is lost forever, an icon whom we cursed” (Goffredo Fofi). Poets like Pasolini and Ungaretti waxed lyrical, each in their own way, over her cry in Roma città aperta, but two other such moments frame her characters’ fates. First, there is the scene towards the end of Bellissima in which she sits on a bench, weeping as she embraces her daughter and looking around bewildered, muttering “Help”; and then there is the final scene of Mamma Roma in which she is restrained by a small crowd once more, stifling her tears as she stares wide-eyed at the new Rome in the distance.

Emiliano Morreale

Program

Thursday 22/06/2023

18:30

Cinema Lumiere - Sala Scorsese

LA PASSIONE DI ANNA MAGNANI

LA PASSIONE DI ANNA MAGNANI

Saturday 24/06/2023

15:30

Europa Cinema

TERESA VENERDÌ

TERESA VENERDÌ

Emiliano Morreale

Sunday 25/06/2023

15:30

Europa Cinema

ROMA CITTÀ APERTA

ROMA CITTÀ APERTA

Introduction by Cinema Ritrovato Young with Emiliano Morreale

Sunday 25/06/2023

21:45

Piazza Maggiore

BELLISSIMA

BELLISSIMA

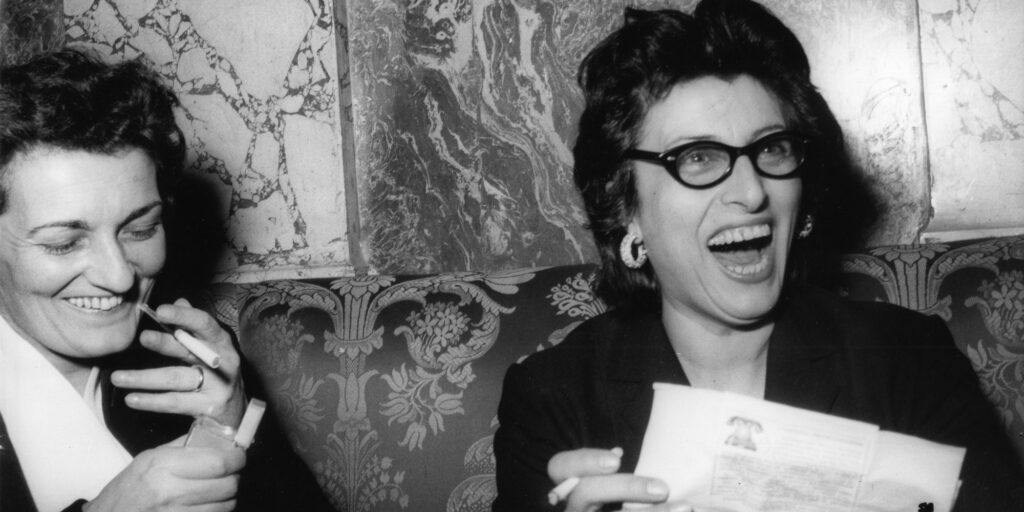

Nan Goldin, Caterina d’Amico e Silvia d’Amico

Monday 26/06/2023

15:30

Europa Cinema

ABBASSO LA RICCHEZZA!

ABBASSO LA RICCHEZZA!

Emiliano Morreale

Tuesday 27/06/2023

11:30

Arlecchino Cinema

ANNA / I VINTI / IL LAVORO

ANNA / I VINTI / IL LAVORO

Caterina d’Amico

Tuesday 27/06/2023

15:30

Europa Cinema

L’ONOREVOLE ANGELINA

L’ONOREVOLE ANGELINA

Emiliano Morreale

Wednesday 28/06/2023

15:30

Europa Cinema

UNA VOCE UMANA / MOLTI SOGNI PER LE STRADE

UNA VOCE UMANA / MOLTI SOGNI PER LE STRADE

Emiliano Morreale

Thursday 29/06/2023

11:00

Arlecchino Cinema

NELLA CITTÀ L’INFERNO

NELLA CITTÀ L’INFERNO

Caterina D’Amico

Thursday 29/06/2023

15:45

Europa Cinema

LE CARROSSE D’OR

LE CARROSSE D’OR

Caterina D’Amico

Friday 30/06/2023

15:30

Europa Cinema

THE ROSE TATTOO

THE ROSE TATTOO

Saturday 01/07/2023

15:30

Europa Cinema

ROMA / LA TRAVERSATA / RISATE DI GIOIA

ROMA / LA TRAVERSATA / RISATE DI GIOIA

Caterina d’Amico