Cinemalibero

Censored, re-edited, confiscated, shown only in the underground circuit, or simply vanished: the films in this year’s programme are the result of endless research and tortuous restoration. The resurrection of these works demonstrates once again that restoration is now an essential vehicle for reconfiguring a transnational space and rewriting the many histories of cinema. In other words, in the combination of its (philological, ethical and technical) practices, restoration can now be considered an act of cultural resistance.

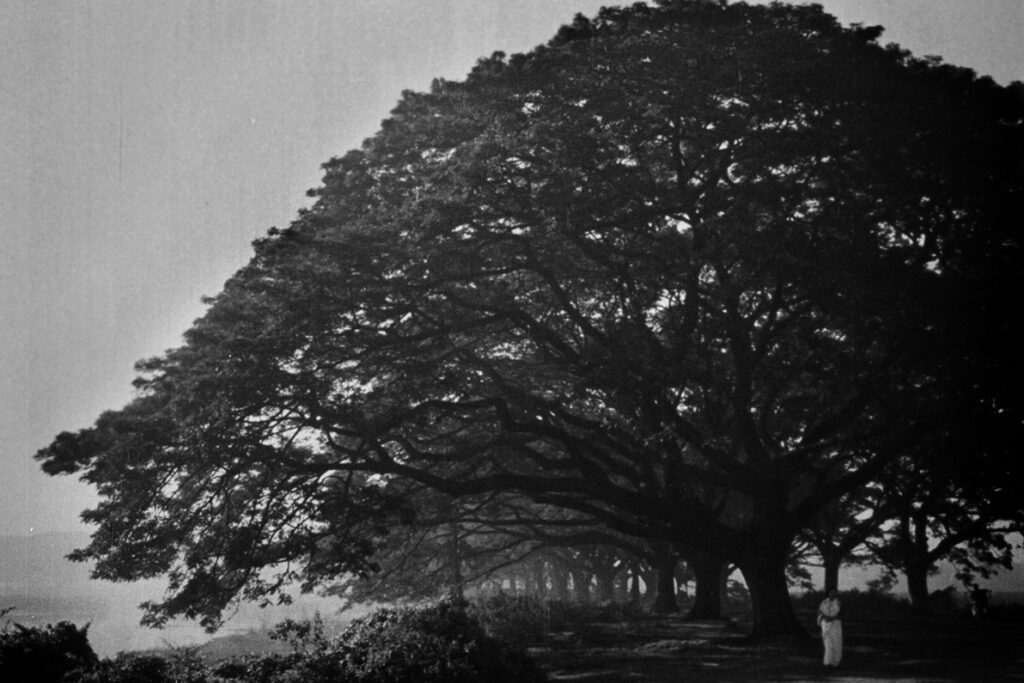

It is precisely in the multiple meanings of resistance – to the horrors of colonial regimes and dictatorships, to cultural dis- placement and the inexorable advance of an all-consuming modernity – that the cinema of the seven great filmmakers in this programme found their raison-d’être. “My memories overflow with life, with intensity”, Ritwik Ghatak writes. “I don’t possess anything else. If I had possessed the gift of writing, if I’d been a poet or a painter, I could have entrusted myself to my eyes as I got older. But I am a filmmaker. I have lost everything. I cannot show anything of what I have seen”. All of Ghatak’s work gravitates around the tragedy of Bengali refugees, displaced from their land after two centuries of English domination. Exiled from their past, the protagonists of Meghe Dhaka Tara cannot imagine a future.

The very existence of Xiao Wu, a petty thief from the provinces crushed under the weight of the relentless advance of the Chinese economy, also seems to suggest a lack of alternatives. With every mouthful of smoke, the protagonist seems to embody the weakening of the heartbeat of a world destined to disappear. If Xiao Wu, the debut of Jia Zhang-ke, never truly existed for the Chinese authorities, Mohammad Reza Aslani’s Shatranj-e Baad is, 45 years after its release, a virtually unseen film.

The representation of violence is at the heart of two films from very distant latitudes: extreme and graphic in Kisapmata, in which the ailing family unit is a clear metaphor for Filipino society under Marcos; and cathartic and satirical in Mueda, Memória e Massacre, the first feature-length film in Mozambique’s cinema and possibly a unique example of one people, including survivors of a massacre, rewriting their own history through a re-enactment. The ‘misunderstood language’ of colonised peoples is at the centre of Sarah Maldoror’s Monangambee, while her other two shorts are the filmmaker’s portraits of Léon Damas and Aimé Césaire, the founding poets of Negritude: “Poetry is my back-up lung”, claims Césaire in Les Masques des mots. We would like to dedicate our programme to Maldoror, a pioneer-warrior of Pan African cinema, a narrator of the struggles for feminist and militant independence.

Cecilia Cenciarelli

Program

Tuesday 25/08/2020

15:00

Arlecchino Cinema

LA MUERTE DE UN BURÓCRATA

LA MUERTE DE UN BURÓCRATA

Luciano Castillo e Cecilia Cenciarelli

Wednesday 26/08/2020

11:00

Arlecchino Cinema

MEGHE DHAKA TARA

MEGHE DHAKA TARA

Wednesday 26/08/2020

21:30

Arlecchino Cinema

LA MUERTE DE UN BURÓCRATA

LA MUERTE DE UN BURÓCRATA

Thursday 27/08/2020

11:00

Arlecchino Cinema

SHATRANJ-E BAAD

SHATRANJ-E BAAD

Gita Aslani Shahrestani (the director’s daughter)

Thursday 27/08/2020

21:30

Arlecchino Cinema

XIAO WU

XIAO WU

Marina Timoteo (Istituto Confucio di Bologna)

Friday 28/08/2020

11:00

Arlecchino Cinema

MUEDA, MEMÓRIA E MASSACRE

MUEDA, MEMÓRIA E MASSACRE

Catarina Simão (on video)

Friday 28/08/2020

21:30

Arlecchino Cinema

SHATRANJ-E BAAD

SHATRANJ-E BAAD

Saturday 29/08/2020

11:00

Arlecchino Cinema

Monangambee / AIMÉ CÉSAIRE / Léon Damas

Monangambee / AIMÉ CÉSAIRE / Léon Damas

Saturday 29/08/2020

21:30

Arlecchino Cinema

MUEDA, MEMÓRIA E MASSACRE

MUEDA, MEMÓRIA E MASSACRE

Sunday 30/08/2020

15:00

Arlecchino Cinema

XIAO WU

XIAO WU

Jia Zhang-ke (in video)

Sunday 30/08/2020

21:30

Arlecchino Cinema

Monangambee / AIMÉ CÉSAIRE, LE MASQUE DES MOTS / Léon G. Damas

Monangambee / AIMÉ CÉSAIRE, LE MASQUE DES MOTS / Léon G. Damas

Monday 31/08/2020

10:45

Arlecchino Cinema

KISAPMATA

KISAPMATA

Monday 31/08/2020

21:30

Arlecchino Cinema

MEGHE DHAKA TARA