A GUIDE TO IL CINEMA RITROVATO 2025

Cecilia Cenciarelli, Gian Luca Farinelli, Ehsan Khoshbakht, Mariann Lewinsky

In Odesa

Where is Seraing? Those visiting the exhibition that the Cineteca di Bologna has dedicated to Georges Simenon will make many surprising discoveries. For example, the links that exist between apparently distant artists, such as the Dardenne brothers and the father of Maigret. It is true that their gazes are different (one Marxist and the other Anarchist) but all three of them were born and raised in Liège; Luc and Jean- Pierre (who never left it) still have their offices in the heart of the city. Simenon described the disorientation experienced by numerous uprooted characters, children of that revolution that made Liège a testing ground for European industrialisation during the 19th century; the Dardennes describe what happens to people over the long term when a large industrial suburb closes down. All their films are set in Seraing, Liège’s industrial suburb. Together, the three of them have recounted 120 years of anthropological transformation, which is still relevant to all of us today.

Where is Seraing? Those visiting the exhibition that the Cineteca di Bologna has dedicated to Georges Simenon will make many surprising discoveries. For example, the links that exist between apparently distant artists, such as the Dardenne brothers and the father of Maigret. It is true that their gazes are different (one Marxist and the other Anarchist) but all three of them were born and raised in Liège; Luc and Jean- Pierre (who never left it) still have their offices in the heart of the city. Simenon described the disorientation experienced by numerous uprooted characters, children of that revolution that made Liège a testing ground for European industrialisation during the 19th century; the Dardennes describe what happens to people over the long term when a large industrial suburb closes down. All their films are set in Seraing, Liège’s industrial suburb. Together, the three of them have recounted 120 years of anthropological transformation, which is still relevant to all of us today.

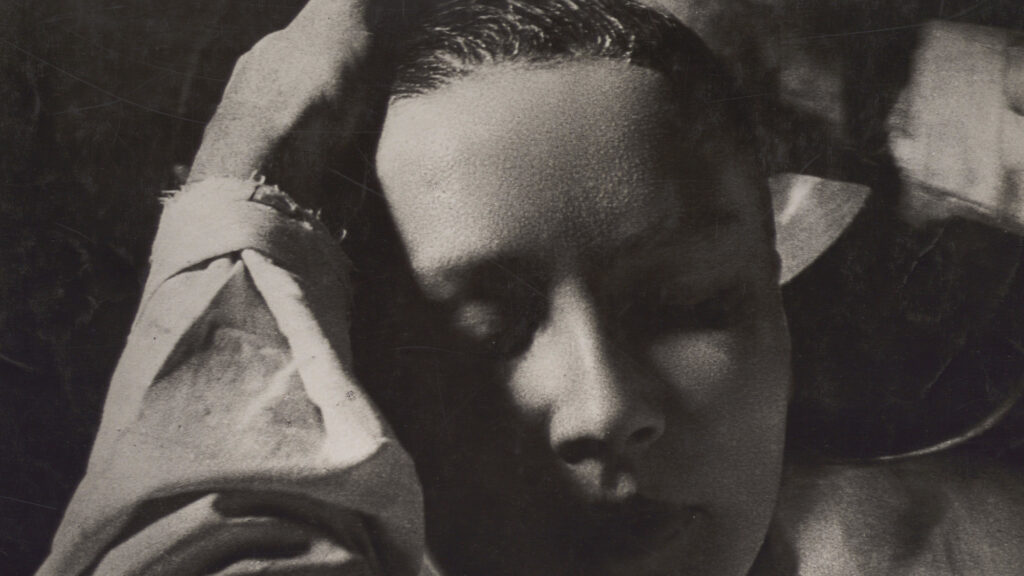

Even more surprising is the discovery of the photographs that Simenon took in Odesa. In the spring of 1933, the writer obtained a visa to enter the Soviet Union and he spent eight days in the historic city facing the Black Sea, which was suffering from a recent famine. After that journey, he wrote The Window Over the Way, one of the rare novels from the period to describe Stalin’s USSR. In Odesa, he also took about 100 photographs, which are extremely valuable because they allow us to see what he saw, as if we were standing next to him, in the streets, markets, and beaches, alongside residents searching for a glimmer of happiness in their free time in the sun.

We cinema dwellers know Odesa – and above all its steps – even if we have never been there. We know that they link the port to the city and that an optical illusion makes them appear longer than they actually are. Thanks to Ėjzenštejn, they are the symbol of a cinema that, 30 years after the Lumières’ invention, was busy experimenting with new languages; above all, however, they are the symbol of an injustice, of weapons killing defenceless civilians, pensioners, women, and children – human lives snuffed out by blind, inhuman violence. Thanks to the section Isaak Babel – Odesa Stories, we learn that in the very same year, that same flight of steps was also utilised by Alexis Granowsky in Jewish Luck (Evreyskoye schastye) to describe an impoverished man’s dream of happiness.

This is Il Cinema Ritrovato: a place to discover that the cinema is much more than we imagined, that cinema heritage is an infinite continent of secret connections between authors and filmmakers who often never even met, a free land in which you can easily run into amazing discoveries, which reveal the beauty and horror of which we are capable. This year as never before, the programme questions who we are, who we want to be, and which side we are on. All these images welling up from the past ask us what kind of world we want for our future and that of our children. Il Cinema Ritrovato is not a cemetery of old films, but the active encounter between a modern audience and the work of the past to ensure that the life and work of so many artists has not been in vain.

The story of Isaak Babel is representative in this regard. He is well-known as a writer but his connection to the cinema is unknown. The retrospective that we dedicate to him is not limited to a single subject, but rather constitutes an open door to an unrepeatable moment, between 1925 and 1930: six years in which very different but equally extraordinary artists such as Eisenstein, Dovzhenko, Vertov and Granowsky lived through difficult and shifting conditions, all the while dreaming of a never-before-imagined art for a better future. The Jews dreamed of an end to Czarist repression, Ukrainians of independence, Communists of a more equal world. They all suffered over their yearning for freedom. Babel was imprisoned and killed in January 1940 by Stalin’s men and his manuscripts were seized and destroyed.

Can cinema heritage come to our aid? Let’s quote Alice Rohrwacher’s introduction to Thierry Frémaux’s miraculous film, Lumière, l’aventure continue!: “The title is not a question, but an exclamation; a surprise and an almost childlike discovery. And this is how we feel after watching the film: like crying out ‘that’s why we go to the cinema!’ Suddenly it feels as though we have just remembered something that we did not know we had forgotten, a sense of meaning in that darkened room that is more profound, but also more primitive and mysterious: we go to the cinema in order to remind ourselves of who we are. This is what the Lumière brothers did when they travelled the world with their wonder machines: they did not do so to demonstrate that their incredible technology made them better than us, but rather in order to see. And by seeing, they also allowed us to see.”

In the Sanatorium

We celebrate the centenary of one of the greatest Polish masters, Wojciech Has, with two screenings, one of which is The Hourglass Sanatorium (Sanatorium pod klepsydrą, 1973) – a film whose essence mirrors the spirit of this festival: visiting the abandoned and forgotten rooms of the unconscious in an old edifice that is the history of cinema. Unlocking each room – filled with intermingling, indistinguishable memories, dreams, and nightmares – leads yet to another. A maze of images that mirror one another and, through infinite reflections, unravel 130 years of how humanity constructed its image, dismantled it now and then, and, at times, in outbursts of senseless violence and widespread repression, destroyed it.

We celebrate the centenary of one of the greatest Polish masters, Wojciech Has, with two screenings, one of which is The Hourglass Sanatorium (Sanatorium pod klepsydrą, 1973) – a film whose essence mirrors the spirit of this festival: visiting the abandoned and forgotten rooms of the unconscious in an old edifice that is the history of cinema. Unlocking each room – filled with intermingling, indistinguishable memories, dreams, and nightmares – leads yet to another. A maze of images that mirror one another and, through infinite reflections, unravel 130 years of how humanity constructed its image, dismantled it now and then, and, at times, in outbursts of senseless violence and widespread repression, destroyed it.

Destroyed too was the life of Polish Jewish writer Bruno Schulz, the author of The Hourglass Sanatorium, shot dead by the Gestapo in 1942. Also destroyed was the life of ethnographic cinema pioneer Friedrich Dalsheim – whose 1936 Die Kopfjager von Borneo will be screened this year – and whose very name was erased from every print of the film as the Nazis consolidated their power. He took his own life two weeks after its premiere.

This is the most fragile of art forms: the lives and reputations of its creators are fragile and fickle; the very materiality of the medium is fragile; and the circulation and reception of films are volatile. Film can fall out of favour – guillotined by ignorance and forgetfulness. No one has captured that so soulfully as Luigi Comencini in Il museo dei sogni (1949) and La valigia dei sogni (1953), which, like The Hourglass Sanatorium, unlock as many forgotten rooms in cinema through the elegiac poetry of remembering things past.

One of the finest portraits of a director ever produced is dedicated to Sergei Paradjanov: Le dernier collage (1995). Officially, Paradjanov was imprisoned for his sexuality – though in truth, it was an act of smothering his blazing passion for life, embodied in astonishing colour and form that baffled and unsettled the ruthless, grey, unimaginative Soviet regime.

One of the most emotionally resonant suppressed films that Il Cinema Ritrovato brings back to life this year is The Postman (Postchi, 1972), whose director, Iranian New Wave pioneer Dariush Mehrjui, was brutally murdered along with his wife at their home in Iran in October 2023 – a murder whose true motive remains unclear. Hauntingly, the film is about a repressed and forgotten man whose fate deliriously culminates in a murderous pitch. Its producer, Mehdi Misaghiyeh, was imprisoned and had his property confiscated after the 1979 Iranian Revolution, simply for being a member of the Bahá’í faith. The film stands as one of many reminders this year of the ever-shrinking tolerance for truthful beauty.

It is not far-fetched to imagine that someone such as Lewis Milestone – a Russian Jew who emigrated to America in 1913 – would be denied entry to the US today. He might even have been deported, for making The North Star (1943), a powerful piece of agitprop about a Ukrainian village’s fight against the invading Third Reich. Milestone, who had witnessed the destruction of WWI, understood that any “war to end all wars” is often just the prelude to another, which claims to do the same. The creator of masterpieces such as Hallelujah, I’m a Bum (1933) and Of Mice and Men (1939), Milestone consistently pleaded for the underdog in the face of economic and social ruin. That empathy alone was enough to place him under pressure and make him a target of McCarthyism – throwing his career into long disarray from which, at least artistically, he barely recovered.

In the early 1980s, two young students organised a “survivors’ banquet” in Los Angeles, inviting all those who had been blacklisted that they could locate. In La dernière fête des blacklistés Marie-Dominique Montel and Christopher Jones show us the beginnings of a work in progress on this precious material.

Hepburn and all the others

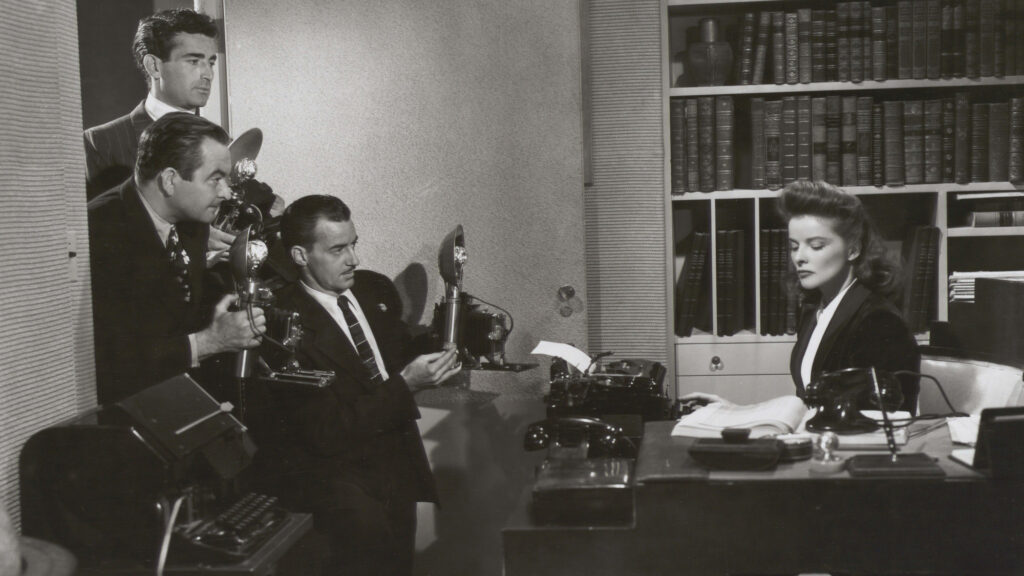

War, with its global upheaval and displacement, finds a surprising treatment in Woman of the Year (1942), where Katharine Hepburn’s shared home with Spencer Tracy becomes a gathering place for international intellectuals and, more poignantly, a refuge for a displaced child whom Tracy, hilariously and tenderly, learns to love. It is a “serious comedy,” sensitively handling the pressing issues of its time. Woman of the Year is one of 11 Katharine Hepburn gems featured in this year’s retrospective, films that illuminate the legacy of this vanguard of feminism: a free-spirited, no-nonsense woman whose best work speaks as much to our time as to hers (including, believe it or not, an early reference to workers being replaced by a proto-AI system).

The gender fluidity of Hepburn – combined with sophistication, intelligence, and a fierce determination for change – is the essence of every film in this programme, carefully curated by one of cinema’s most influential critics, Molly Haskell. Her landmark book From Reverence to Rape played as pivotal a role in reshaping the discourse on women in cinema as Hepburn’s films did in the 1930s and 1940s.

If Hollywood film noir is known for its stylised gaze fixed on an ideal, unattainable, and often destructive female figure – the femme fatale and her variations – the Scandinavian variant, presented at Bologna in the section Norden Noir, thanks to a collaboration between the film archives of Denmark, Norway and Sweden, adds a remarkable twist. While borrowing from classical archetypes, it infuses them with local nuances and reframes them through a Nordic lens – and unexpectedly, two of its earliest examples were directed by women: the Danish Bodil Ipsen and the Norwegian Edith Carlmar.

This year, for the first time, we are dedicating a retrospective to an auteur who is still very active: Coline Serreau, actress, director, but first and foremost a musician and a trapeze artist. It is an opportunity to discover the curiosity, radical strength, intelligence and astounding vision of a director who knows how to make us laugh and how to make us think, who never tires of watching and studying us, to overturn that which is wrong, to propose alternative solutions. Her films cannot be classified, and that’s why we like them.

At the age of 30, Márta Mészáros’ voice was already nearly fully formed. We present three precious restored shorts by the Hungarian director, which reveal her grace in narrating the most fragile human experiences in new and unconventional ways. With a strength comparable to that of her contemporaries Agnès Varda, Larisa Shepitko and Věra Chytilová, Mészáros would go on to put female representation – in its identitarian, sexual, political and militant dimensions – at the centre of her cinema. This can be seen as early as In the Lőrinc Spinnery (A Lőrinci fonoban, 1972), where we witness the silent unfolding of a day in the life of the female workers at a textile factory. No longer idealised objects, but real and individual presences, endowed with strength and vulnerability, the workers of the Hungarian town of Lőrinci exemplify a new gender consciousness.

Mészáros is one of the many female protagonists at Il Cinema Ritrovato this year, which gives ample space not only to female directors but also authors, screenwriters and producers. And this is an aspect we will continue to emphasise until every talented artist from every era and latitude has emerged from the shadows to which they have been relegated by cinema history. This is the case with Mara Blasetti, the legendary Italian production manager to whom Michela Zegna has dedicated a portrait. Also Sinhalese director Sumitra Peries, whose Girls (Gehenu Lamai, 1978) we will be discovering, thanks to the ever-improving possibilities offered by modern restoration techniques. It is a talented debut work that looks at the broken dreams and the end of innocence of a young woman in rural Sri Lanka in the 1960s. Female adolescence during a time of war once again takes centre stage in Jocelyne Saab’s debut feature-length work, The Razor’s Edge (Ghazl el-banat, 1985), set in a Beirut full of wonder and destruction, while The Arch (Dong fu ren, 1968) denounces the cruelty of the social conventions that crush the voice and identity of a recently widowed woman in 17th-century China. The film marked the debut of Shu Shuen Tang, the first female director from Hong Kong to receive international recognition, at a time when Hong Kong and Chinese cinemas were strictly male dominated.

Complex female portraits are also to be found in two films by Mikio Naruse. The first, A Woman’s Sorrow (Nyonin aishu, 1937), is part of the section curated by Alexander Jacoby and Johan Nordström that investigates the crucial five-year period (1935-39) in the career of the director preceding the outbreak of war; the film tells the story of an arranged marriage within the oppressive constraints of Japanese society. The second is the recently restored Floating Clouds (Ukigumo, 1956), featuring a standout performance by Hideko Takamine, one of Japan’s greatest actresses. She made her debut at the age of five, became the most famous child star in Japan, managed not to be overwhelmed by fame and went on to have an outstanding career as an actress in over 160 films, working with many of her nation’s greatest filmmakers, from Ozu to Kinoshita, from Kurosawa to Naruse, who directed her 17 times in total.

It is hard not to acknowledge the talent of Zoe Akins, poet, playwright, screenwriter and winner of a Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 1935, whose vitriolic comedy The Greeks Had a Word for It – which sees three young women rent a luxurious apartment with the aim of ensnaring a rich husband – was adapted from the stage to the big screen in 1932 by Lowell Sherman, substituting It for Them in the title and unleashing Coco Chanel to dress the three female leads. It would later serve as inspiration for both Moon Over Miami (1941) and How to Marry a Millionaire (1953). Akins was also the screenwriter of another film at Bologna this year, Christopher Strong (1933), Katharine Hepburn’s second screen outing, the story of a clash between love and work in a society where a woman’s independence is not to be expected. It was directed by Dorothy Arzner (also present in the A Hundred Years Ago section as the screenwriter of The Red Kimona), the most important female director working in the Hollywood of the 1920s and 1930s. We’ll round off this round up of female artists with a prima donna of British and American theatre who was too unwieldy even for Hollywood: Tallulah Bankhead, famous for smoking 120 cigarettes a day, her alcohol and drug abuse, her exhibitionism – practised above all while on stage – her female lovers, which included Billie Holiday, and her male lovers, including Johnny Weissmuller, the best screen Tarzan. Joan Crawford said of her: “We all adored her. We were fascinated by her, but we were scared to death of her, too … She had such authority, as if she ruled the earth, as if she was the first woman on the moon.” So unique that Margo Channing, the character played by Bette Davis in All About Eve, was inspired by her, at least that’s what Tallulah claims … We will be screening Lifeboat (1944), her greatest cinematic success, which was also one of the few failures of Hitchcock’s career. Seen today, not only are we captivated by her performance but also by the depth of the film, an apologue about having to choose a side during the war: after 80 years, a theme that has dramatically returned to the fore.

Debut films and unique works

Giuseppe Bertolucci, an unknown 21-year-old actor in Jean- Claude Biette’s short film La partenza (1968), considered a debut to be a magical moment in the life of any filmmaker, because in that first work they express, in a nutshell, the entire creative universe of their art. This year’s programme is rich in debut works that appear to confirm this theory. In the 1925 section we find extraordinary first works by three future greats, Jean Renoir, Josef von Sternberg and Alfred Hitchcock – The Whirlpool of Fate (La Fille de l’eau), The Salvation Hunters and The Pleasure Garden. The selection continues with another masterpiece from 1925, Grass: A Nation’s Battle for Life, by the duo of Schoedsack and Cooper, whose personal and artistic adventure is recounted in the documentary King Kong, le coeur des ténèbres.

There are also debuts from Max Ophüls, Die verliebte Firma (1931), a crackling comedy about the production of a musical; from Niki de Saint Phalle, Daddy (1973), a liberating film about the patriarchy; from Charles Burnett, Killer of Sheep (1978), a touching yet bitter portrait of the life of an African-American family in Los Angeles; from Donald Cammell and Nicolas Roeg, Performance (1970), a film so shocking that Warner waited two years before distributing it. Violent and elegant, almost a documentary about Mick Jagger and Anita Pallenberg – with a fantastic soundtrack by Jack Nitzsche, featuring songs by Randy Newman, Ry Cooder and Jagger himself – Performance is a film unlike anything that had come before, but which influenced and continues to influence those that came after.

The first works of Aleksandr Askoldov and John Bidgood represent the entire filmographies of two immensely talented directors who, unfortunately, only got the chance to make one film each. The Commissar (Komissar), based on the Vasily Grossman short story V gorode Berdicheve (1934), was shot by Askoldov in 1967 but supressed by the censor until 1988, when it won the Silver Bear at the Berlinale. There are the USSR and the Ukraine, there are Jews and Communists, and then there is the protagonist, the Party Commissar who, in the middle of the civil war, has to give birth in the house of a poor craftsman: disenchantment, creativity, dreams and reality, a heartbreakingly expressive happiness. And then there is Pink Narcissus, written and directed by photographer John Bidgood, shot on 8mm between 1963 and 1970, distributed without the consent of its author who considered it a failure and signed it “Anonymous”. In exploring the fantasies of a young gay New Yorker, it created a vital and previously unseen chromatic universe, soon becoming a cult film.

From the page to the screen

A fatal attraction pushes filmmakers to draw inspiration from literature. It has always been this way, even when the undertaking must have seemed impossible: as far back as the 1905 section we find adaptations of highly popular 19th-century novels (The Hunchback of Notre Dame, Les Miserables), condensed into those few brief minutes of the first silent films; while in the 1925 section Henri Fescourt’s sumptuous cinematic transposition of Les Miserables – lasting over six hours– is the serial at this edition of Il Cinema Ritrovato. Another titanic endeavour was Die Buddenbrooks (1923), the adaptation of the Thomas Mann masterpiece by Gerhard Lamprecht, director and founder of Deutsche Kinemathek, which will be presented in a newly restored version. The delightful Turkish film Aysel Bataklı Damın Kızı (1934) boasts a dual connection to literature: inspired by a story by Selma Lagerlöf, its screenplay was written by the poet Nazım Hikmet.

We ask ourselves why La Verite sur Bebe Donge (1952) is not part of the canon of cinema history. Based on the eponymous novel by Georges Simenon, it is one of the most successful adaptations of his work. Everything is perfect: Henri Decoin’s direction, the screenplay, the portrait of the French provinces, full of falseness and corruption, the harshness and repentance of industrialist and serial cheater François Donge, magnificently played by Jean Gabin. But the film surpasses itself thanks to Danielle Darrieux, here at the height of her art. The actress, who within a few months would star in two masterpieces by Max Ophüls – La Maison Tellier, an episode from Le Plaisir, and Madame de… – gives incredible depth to her character, a fragility so human as to make her eternal. In Italy the film was given the title La follia di Roberta Donge (The Madness of Roberta Donge), eight minutes were cut and many lines of dialogue changed, transforming Mrs Donge’s rebellion into a case of insanity.

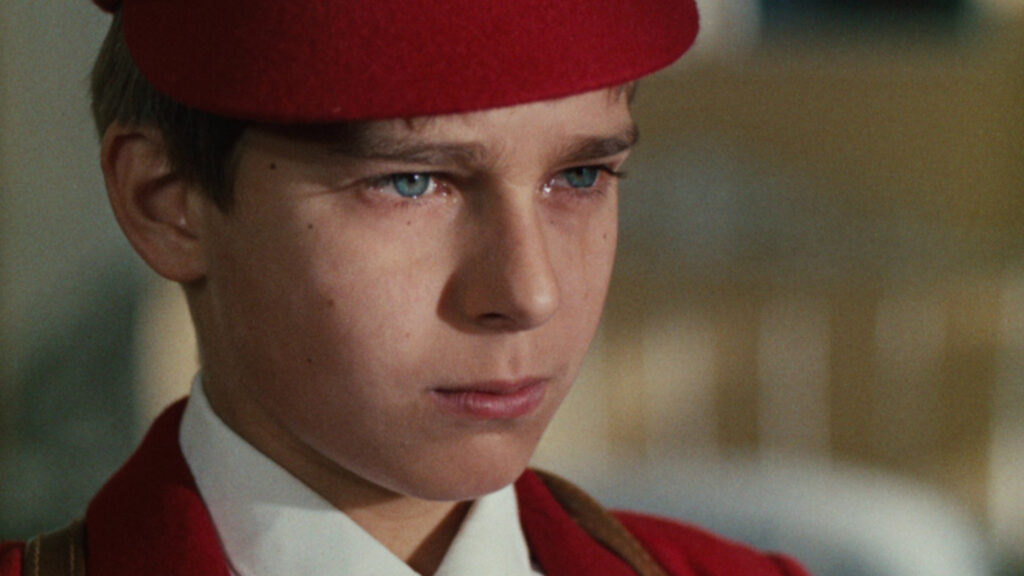

In the relationship between the written page and cinema, the most “unreasonable” challenge is that of Wojciech Has, who adapted Potocki’s 19th-century novel The Manuscript Found in Saragossa (Rękopis znaleziony w Saragossie) into a labyrinthine, dreamlike and surreal film, in which the viewer is transported by the unbridled playful genius of the Polish director. And finally there is Pinocchio, Comencini’s version, conceived as five 55-minute episodes for television and reduced to just over two hours for the cinema version. For those Italians who watched it on television as children, Comencini’s version is more important than Collodi’s book. It is the perfect adaptation of the peasant fairy tale, in which every actor (Manfredi, Lollobrigida, Stander, De Sica, Franchi and Ingrassia) excels in bringing their characters to life.

Children

More introspective and psychological is the story of Bobita (1965), one of the three magnificent shorts by Márta Mészáros. Through the eyes of a young boy, it explores the emotional reawake ning of a socialist society in which life seems to be silently moulded and suffocated by conformism and ideological rigidity. Children are not only a constant presence in the free and anarchic early cinema, but its authentic and natural stars. Lively, capricious and mischievous, they cunningly evade the rules and punishments imposed by adults. Let’s try to imagine the adventures of the young assistant pastry chef in Les Farces de Toto Gate-Sauce (1905) accompanied by the musical theme to Pinocchio, composed by Fiorenzo Carpi – a prank that certainly would have pleased Comencini, a filmmaker who was an enthusiast of silent cinema and understood how to represent childhood. From his first short Bambini in citta (1946) to Misunderstood (Incompreso, 1966) – Isabelle Huppert recently confided that seeing this film continues to move her just as it did when she was a child – to the TV series I bambini e noi (1970), a dress rehearsal for Pinocchio, to Eugenio (Voltati Eugenio), Comencini always knew how to observe children, placing himself at their level and on their side.

ning of a socialist society in which life seems to be silently moulded and suffocated by conformism and ideological rigidity. Children are not only a constant presence in the free and anarchic early cinema, but its authentic and natural stars. Lively, capricious and mischievous, they cunningly evade the rules and punishments imposed by adults. Let’s try to imagine the adventures of the young assistant pastry chef in Les Farces de Toto Gate-Sauce (1905) accompanied by the musical theme to Pinocchio, composed by Fiorenzo Carpi – a prank that certainly would have pleased Comencini, a filmmaker who was an enthusiast of silent cinema and understood how to represent childhood. From his first short Bambini in citta (1946) to Misunderstood (Incompreso, 1966) – Isabelle Huppert recently confided that seeing this film continues to move her just as it did when she was a child – to the TV series I bambini e noi (1970), a dress rehearsal for Pinocchio, to Eugenio (Voltati Eugenio), Comencini always knew how to observe children, placing himself at their level and on their side.

On the other hand, the childhood depicted by Iranian filmmaker and playwright Bahram Beyzaie is one defined by absence (family and personal, but also institutional and social). Strongly influenced by theatre – both traditional Persian and modern experimentalism – Beyzaie follows two children over the course of one day in the outskirts of Tehran, amid the dirt and the ruins of a world that is collapsing. Dense in symbolism, The Journey (Safar, 1972) is a small film of extraordinary visual beauty. Many more children appear throughout this year’s programme, from the films of Il Cinema Ritrovato Kids to Truffaut’s debut (Les Mistons, 1957), to the hilarious silent comedies of Laurel and Hardy, adults who went back to being children.

The Mood of the Times

The mood of th e times sticks to a film; it is like its identity card, proof of its veracity. This is patently evident in newsreels, which recount events destined to become part of history. To celebrate Gaumont’s 130th anniversary, we asked its archive for 80 minutes of newsreels from 1939. This was not just any year. In the newsreels, well-known events sit alongside lesser-known but still significant ones, together with a plethora of minor news items about ordinary people who, unbeknownst to them, were living through the final moments of peace. Let’s take another example of the mood of the times, Il pianto delle zitelle (1939), a stunning documentary about an archaic religious rite linked to springtime, directed by the photographer Giacomo Pozzi-Bellini; it won the best documentary prize at Venice and was censored under Fascism; Michelangelo Antonioni considered it the very first example of neorealist cinema. In it we see the faces of women in prayer – their gestures, their voices singing songs, the handkerchiefs that crown their heads. It is a precious, unintentional testimony of a world that once was but that no longer exists.

e times sticks to a film; it is like its identity card, proof of its veracity. This is patently evident in newsreels, which recount events destined to become part of history. To celebrate Gaumont’s 130th anniversary, we asked its archive for 80 minutes of newsreels from 1939. This was not just any year. In the newsreels, well-known events sit alongside lesser-known but still significant ones, together with a plethora of minor news items about ordinary people who, unbeknownst to them, were living through the final moments of peace. Let’s take another example of the mood of the times, Il pianto delle zitelle (1939), a stunning documentary about an archaic religious rite linked to springtime, directed by the photographer Giacomo Pozzi-Bellini; it won the best documentary prize at Venice and was censored under Fascism; Michelangelo Antonioni considered it the very first example of neorealist cinema. In it we see the faces of women in prayer – their gestures, their voices singing songs, the handkerchiefs that crown their heads. It is a precious, unintentional testimony of a world that once was but that no longer exists.

Another example would be the four shorts made between 1931 and 1945 by two extraordinary experimenters, Franciszka and Stefan Themerson, a pair of artists who approached art from an interdisciplinary perspective. The vibrant and poetic Europa (1931) is an anguished cry against intolerance and violence as well as a heartfelt appeal to the continent to offer refuge to everyone; Calling Mr. Smith (1943) employs the tools of abstraction and the avant-garde to invoke the spectator in a lament against the atrocities of the Nazi regime.

Even more surprising is Till We Meet Again (1944), in which everything is improbable and artificial, beginning with the reconstruction in Hollywood of France occupied by the Nazis. However, Frank Borzage’s genius and the involvement of a good number of artists who had fled Europe, as in the case of Casablanca, gives the film a sense of truth and urgency that, after a few minutes, makes us forget that we live in 2025.

Reality also creates unexpected connections, such as that between José Antonio Nieves Conde’s El inquilino and Luigi Comencini’s La finestra sul Luna Park. Both were made in 1957, the first in Madrid and the second in Rome, and both tell of the effects of the economic boom and housing speculation on the lives of individuals. Franco’s censors put pressure on the first and changed its meaning; the second was a failure at the box office but marked the true beginning of Comencini’s career.

The mood of the times follows many surprising paths. In A la memoire du rock (1963), Francois Reichenbach takes us to a large concert hall in Paris and observes the audience. In order to bring us closer to what is going on, he does not make use of the concert’s rock music but, paradoxically, Boccherini’s String Quintet no. 5, in order to convey the pure joy experienced by the young spectators.

Sometimes the mood of the times can only be expressed through colour, and this year we offer you the absolute peaks of beauty: from the profound, tragic, and oneiric Technicolor of Duel in the Sun (1948), which perfectly encapsulates the late- 1940s, to the sweetened colour of Artists and Models (1955) and the glossy and plasticised certainties of the 1950s. Just a few minutes of El grito (1968) are all that are required for us to awaken in Mexico City in July 1968, during the fiery days that shook Mexico before the beginning of the Olympic Games.

We journey to India in 1970 in Days and Nights in the Forest (Aranyer Din Ratri), a miraculous film that depicts the complexity of the country with a lightness of touch of which only a master such as Satyajit Ray is capable. In the film we see Sharmila Tagore – great granddaughter of Rabindranath Tagore, winner of the Nobel Prize in literature – one of Ray’s favourite actresses and one of Bollywood’s most famous faces. In the film, she is mysterious, cerebral, magnetic, and much more charming and intelligent than the male characters who court her.

Sometimes it is an actor who incarnates an era, even while playing vastly different roles. This is the case of Jack Nicholson, who played the unheroic Robert Eroica Dupea in Five Easy Pieces (1970), and then five years later the heroic R.P. McMurphy in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. Two epoch- making films.

Sometimes a film takes us somewhere we have never been, or to the heart of something we have forgotten, as in Ferid Boughedir’s precious documentary Caméra arabe (1987), which transports us to the end of the Arab cinema’s golden age, marked by a whole generation of masters such as Mohammed Lakhdar-Hamina, Mahmoud Ben Mahmoud, Abdellatif Ben Ammar, Merzak Allouache, Mohammad Malas and Youssef Chahine. Among the directors featured in Camera arabe is a young and eloquent Nouri Bouzid, whose restoration of L’Homme de Cendre (1986) – a film capable of shattering many of the taboos of Arab cinema – will be shown this year for the first time.

In this journey through time, we cannot say which is the best film in Il Cinema Ritrovato, but at least we know which is the worst: According to the respected critic Morando Morandini, Arrapaho “is the worst film in the history of Italian cinema”, a trash-film masterpiece from the early 1980s, made on a miniscule budget by Ciro Ippolito.

To Be or Not to Be

Our festival takes place over three weeks, and for eight days makes use of eight cinemas running from morning to night, as well as two arenas dedicated to open-air screenings: Piazzetta Pasolini and Piazza Maggiore. It is animated not only by screenings, but also encounters in the fine company of artists and professionals, cinema lectures, performances, and a packed programme of cine-concerts. It is incorrect to say that cinema is not a performance art; rather, one of things that makes Il Cinema Ritrovato special is the attention paid to every single seance, to the auditorium where it takes place and the quality of the introductions and the screenings. Once again this year, many films will be screened on celluloid (for some years now a whole section has been dedicated to smaller gauges), while all the silent films will have live accompaniment by the most accomplished specialists of this wonderful art, which restores music to the image. This year, we will also have a narrator, Julie Linquette, who will present Georges Méliès films and help recreate the atmosphere of early cinema performances, when every projection was magic.

Our festival takes place over three weeks, and for eight days makes use of eight cinemas running from morning to night, as well as two arenas dedicated to open-air screenings: Piazzetta Pasolini and Piazza Maggiore. It is animated not only by screenings, but also encounters in the fine company of artists and professionals, cinema lectures, performances, and a packed programme of cine-concerts. It is incorrect to say that cinema is not a performance art; rather, one of things that makes Il Cinema Ritrovato special is the attention paid to every single seance, to the auditorium where it takes place and the quality of the introductions and the screenings. Once again this year, many films will be screened on celluloid (for some years now a whole section has been dedicated to smaller gauges), while all the silent films will have live accompaniment by the most accomplished specialists of this wonderful art, which restores music to the image. This year, we will also have a narrator, Julie Linquette, who will present Georges Méliès films and help recreate the atmosphere of early cinema performances, when every projection was magic.

The evenings under the stars in Piazza Maggiore on 21 and 26 June will certainly be enchanted, with the 70mm projection of Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), and The Gold Rush, which, following a lengthy restoration, returns the film to how it was on its original release, 100 years ago, together with live accompaniment by the Orchestra del Teatro Comunale di Bologna.

In recent years “community”, like all important words, has been drained of its archaic and sacred meaning and become a monster in the hands of monsters. Yet we cannot think of another word to define us: the Bolognese audience, the international audience, the archives, libraries, curators of the various sections, and the authors of this object called a catalogue, which you are holding in your hands and which is the fruit of the passionate, expert and obsessive work of an amazing editorial team who keep this utopia alive. They work all year round to produce an impossible book in which films (including the most forgotten titles) and deep, wide-ranging knowledge are brought together in a joyous act of sharing and transmission.

We speak of a utopia come true because the Cineteca has grown and improved alongside Il Cinema Ritrovato during these past 39 years. In the beginning it was just the Cinema Lumière in via Pietralata, then the two auditoriums of Piazzetta Pasolini, the screenings in the Cortile d’onore of Palazzo d’Accursio, and the screen in Piazza Maggiore. These cultural spaces paved the way for the Modernissimo project, an auditorium of 333 seats and an exhibition space of 1,500 square metres.

During its first 12 months, the Modernissimo sold 146,000 tickets – a record for a single screen cinema in Italy. Translation: the Modernissimo, with its programme of film history, without first-run films, was by a long margin the most successful single- screen cinema in Italy, winning the Golden Ticket award. This is the result of a 40-year history, proving that culture needs time and love, that if we plant seeds, we have to protect them and give them time to bear abundant fruit. It wasn’t just a few people who believed; we were all united, and now we can prepare for Il Cinema Ritrovato’s 40th anniversary, which promises to be an enormous celebration!

In the meantime, happy 39th Cinema Ritrovato to you all!