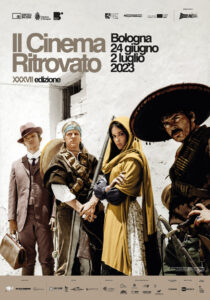

A GUIDE TO IL CINEMA RITROVATO 2023

The world of Il Cinema Ritrovato is not too dissimilar from Jean Renoir’s The Golden Coach (Le Carosse d’or, 1952), a film to be screened this year. Like Renoir’s joyous and colourful ode to the world of stage and to life itself, it is impossible for us to separate the art (in our case, cinema) from the people who have created it (some will be with us in Bologna), those who have preserved and restored it (many of them will be with us in Bologna), and finally those who watch it, discuss it and bring these films into their daily lives – in other words, you! It’s from your delight that the festival gets its inspiration. So let the wheels of the golden coach roll again. You are cordially welcome to our banquet of cinema!

The coach will take you on a nine-day journey across different landscapes of innermost human feelings and expansive geographical terrains, interchanging effortlessly to give us that most precious of interventions – the machine of empathy. Within that mechanism, the large and small, the celebrated and the forgotten, find equal value. The festival selection shows films about nations and civilisations being built (The Covered Wagon, 1923). It also shows how matches are made (Zündhölzer, 1960). On the horizon of celluloid, with the world under construction before our very eyes, the macro and the micro universes hold equal weight.

The earliest images of Il Cinema Ritrovato appear in the time capsules of 1903 where the integrity of image-making turns the most insignificant events into moments of wonder and rebirth. The shadows and flickering lights become the story itself as in Warning Shadows (Schatten, Arthur Robison, 1923). This is subsequently taken to the limit, as in the 3D noir I, the Jury (1953) where, in the hands of the Rembrandt of cinematography, John Alton, the shadow play becomes the meaning of what we see. He takes over, dwarfs the story, plot and characters, tells us to forget about them, then draws us into the dream zone of hard-edged blacks and tilted angles.

Bologna’s Gravitational Pulls

In Il Cinema Ritrovato’s solar system, our gravitation comes not just from one sun but from many. These “idols of flesh and blood” who are also called “stars”, burning bright long after they are gone, are not merely famous or iconic actors, but an embodiment of millions of identities projected into one. In that sense, a long overdue tribute to Anna Magnani, the ultimate goddess of the screen, is now realised in a dazzling array of films. It captures the essence of her combustible charisma and her breathtaking transitions from neorealism to comedies to intimate dramas. Emiliano Morreale’s wide-ranging selection is an investigation into the persona who mesmerised the world and defined Italianness long before Sophia Loren.

Yet, this is just the beginning as the list of this year’s stars is endless: Audrey Hepburn, Burt Lancaster, Totò, Marcello Mastroianni, Montgomery Clift, Deborah Kerr, Ivan Mosjoukine, Brigitte Bardot, Spencer Tracy, Kazuo Hasegawa, Ingrid Bergman, Gregory Peck, James Dean, Susan Taslimi (“the Iranian Anna Magnani”), John Wayne, Barbara Stanwyck, Gary Cooper, Lino Ventura, Lyda Borelli, Tyrone Power and Jean-Paul Belmondo.

Long Ago, But Not Far Away

This year, A Hundred Years Ago strand has been entrusted to curator Oliver Hanley whose imaginative reassessment of the year 1923 in movies has led to seven wide-ranging and all-encompassing “chapters”, revisiting the treasures, curiosities and oddities of that year with fresh eyes. Who doesn’t want to see a film whose director is called Ferenc Futurista, the man behind the Czechoslovak Za oponou smrti (1923)? What a perfect name that would make for the inventor of the movies.

We see great names of cinema – Eisenstein and Epstein – taking their first or second measured and steady steps towards brilliance and mastery. As the movies age, the divergence of styles reveals a dizzying range of possibilities in the medium, from essayistic satire to expressionist collectivism and feminist impressionism. In between, there are epic films, westerns, comedies and melodramas as sophisticated and solid as the ones that would dominate the screens in the following decades.

We don’t leave the “silent” in silence. The musical interpretation of 175 silent titles (some of which, in fact, have no titles) is a mammoth task but with our exceptionally talented group of musicians on board, we are confident that this will also be a music festival of sorts. You can make your way to Sala Mastroianni for intimate piano or piano/percussion accompaniment. In the Piazzetta Pasolini, slightly larger ensembles respond to the films screened by the carbon arc projector. And finally, in the Piazza Maggiore, two masterpieces from 1925 – Ernst Lubitsch’s Lady

Windermere’s Fan and Henry King’s Stella Dallas – will be treats for the eyes and ears, thanks to new restorations and new scores to be performed by a full orchestra.

The Open Seas of Cinema

Albert Samama Chikli’s name was first a quiet whisper. Now, it’s a full song, thanks to a newly initiated Cineteca di Bologna project dedicated to preserving the work of this Tunisian pioneer of film and photography. This year, we delve deeper into his non-fiction and widely distributed films made between 1905 and 1915, reminding ourselves that he is far more than a marginal figure, rather a name worthy of the canon of the true pioneers of cinema.

His films will not be our only stop in Africa. The dust and dirt of time have been removed from more world cinema masterpieces in the Cinemalibero section. They take us on an exhilaratingly rich journey from the shores of the Atlantic Ocean in Senegal to those of the Caspian Sea in Iran via some unexpected stops in the Arab world.

In Senegal, Ousmane Sembène’s biting critique of the colonialist forces of both the Christian and Islamic powers and their devastating impact on the sub-Saharan communities in the newly restored The Outsiders (Ceddo, 1977) reaffirmed its director’s sharp perspective and nuanced take on colonialism. The long-awaited restoration of The Dupes (Al-Makhdu’un, by Egyptian Tewfik Saleh, 1972) should shed light on Syrian cinema, one of the least-known in the Middle East. Taking as its subject three Palestinian refugees in search of a better life, the film is, nevertheless, an emblematic example of Pan-Arab cinema and the fascinating exchanges between Arab nations in the 1970s.

The journey takes a rapid turn northeast and ends with two mysterious and ceremonial masterpieces by Iranian Bahram Beyzaie, The Stranger and the Fog (Gharibeh va meh, 1974) and The Ballad of Tara (Cherike-ye Tara, 1979), offering a feminist perspective on the centuries-old rituals of a patriarchal land.

From Shadow to Desire

The director focus remains one of the most popular ways of showing films in Bologna. This year we have two parallel and, in many ways, similar trajectories with bodies of work that stretch from silent cinema all the way to CinemaScope – even if the filmmakers in question worked thousands of miles apart, and under very different circumstances. What the cinemas of Rouben Mamoulian and Teinosuke Kinugasa have in a common is a restless search for innovation in storytelling and form, a thirst for experimentation across a wide range of popular genres. They both deal with literary adaptations, films about the performing arts, and in period dramas they achieve wonders. While Mamoulian’s work is relatively well-known, Kinugasa’s films have been barely explored outside Japan. Seeing their work in tandem can reveal how easily they transitioned from silent to sound, from genre to genre, always maintaining a strong signature style that should make these programmes two of the vital stories we have to tell this year.

As I Was Moving Ahead, I Saw Glimpses of Beauty

Mamoulian was of Armenian origin. He worked in different countries before arriving in America. The idea of movement of talent, whether by choice or through force, is a central narrative of this year’s festival. The Russian Fedor Ozep made Amok (1934) in Paris while Renoir had to leave behind his work and native France to become a total outsider in Hollywood, a period of near rejection that we will focus on by screening The Woman on the Beach (1947).

Unlike Renoir, Hitchcock was fully embraced by Hollywood where he continued to stay busy for four decades, an intensely creative period from which Spellbound (1945), his eighth American film, screens at the festival in a new restoration. After Hitchcock’s departure from England, it was up to the duo of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger (a Jewish Hungarian who arrived in London in 1935 as a stateless person) to fill the gap with their erotically charged fantasies of unmapped territories of the mind. A brand-new print of Black Narcissus (1947), which will be spooled into the projector for the first time in the Piazza Maggiore, is an example of their breathtaking poetry in ravishing Technicolor. But British cinema before the glories of the 1940s remains underexplored territory, and a celebration of Powell’s solo career before his fateful encounter with Pressburger will take us on a surprisingly rich and witty journey into British life in the 1930s.

Lukas Foerster’s programme on German musicals of the early 1930s last year shattered the stereotypical notion that Germans are not in their best element when doing comedy. This year he offers a new angle into that period by following the sad tale of the creators of those films in a later phase of their career. Now in exile in the neighbouring countries of Austria, Hungary and Czechoslovakia, their films are love letters “to the benefits of irreverence and to the pleasures provided by the jazz and booze-fuelled urban nightlife,” as Lukas puts it. There’ll be more laughter, more foot-tapping joy in the cinema, this time with a pinch of gloom, knowing that soon these great talents will be pushed even further, careers and lives destroyed following Nazi Germany’s expansionist aggression. That’s how the Berlin-born Hermann Kosterlitz was first pushed to Austria and soon to Hollywood where he worked under the new screen name of Henry Koster. The Jewish German in exile Robert Siodmak had his classic American noir Suspect (1945) in cinemas when his hometown of Dresden was reduced to ashes during the bombings of allied forces. The film, which we will also play, brims with fear, fatal blows threaten the flow of life, but it also resounds with integrity, acknowledging the darkness within.

Desolation Row

With the invasion of Ukraine and subsequent war dragged tragically into its second year, images of blind atrocity and the carnage of war are more relevant than ever. Cross of Iron (1977), Sam Peckinpah’s sardonic and brutal rejection of the madness of war, was deemed too bleak for its time but it didn’t stop Orson Welles from sending him a telegram, calling it the finest anti-war film he had ever seen. Yet, the most moving pacificist message among this year’s films is in The Burmese Harp (Biruma no tategoto, 1956); Kon Ichikawa’s deeply humanist rejection of bloodshed is a work of absolute lyrical humanism.

The trail of desolation on land and people that a war leaves behind is unforgettably captured in a series of Swiss films we’ll be showing this year. Frédéric Maire’s programme centres on a pioneering Swiss film production company, Praesens-Film, still operating and celebrating a centenary that back in the day produced films by Hans Richter, Walter Ruttmann, Bertolt Brecht, and Fred Zinnemann. This programme’s focus is on the highlights of the collaboration between the studio and the director Leopold Lindtberg in a series of controversial and momentous films that now, to their credit, have gained new meaning. The supreme example is The Last Chance (Die letzte Chance, 1945), a touching tale of refugees in wartime Switzerland.

The thread of anti-war films continues with Stanley Kubrick’s Fear and Desire (1952). You may know the film well, but you probably don’t know the version we’ll be screening this year.

Lost Minutes, Found Hours

The programme contains some films that, for years, couldn’t be seen in the way that was originally intended. We’re talking about missing scenes, alternative cuts, truncated copies and, occasionally, censored classics. This year, we present some of those vanished and buried lost minutes of film history brought back to life. So Kubrick’s early classic is now ten minutes longer than the version you may have seen before, the way it was shown at the Venice Film Festival in 1952. Or Mid-Century Loves (Amori di mezzo secolo, 1954), the Italian anthology film among whose directors are Roberto Rossellini and Antonio Pietrangeli, is now 18 minutes longer than the existing copies, restored to its original cut and structure.

Sometimes the case is even more baffling. How come Time of the Heathen (Peter Kass, 1961), the tragic escape of a wrongly accused man and deaf black boy in the deep south that gradually shifts into a hallucinatory plea for tolerance and pacifism, has not been seen since its original run? What a small miracle of a film!

Strange Fruits

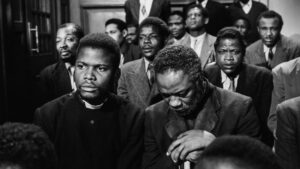

Time of the Heathen’s critique of racial injustice and segregation is not alone in this year’s programme. Cry, the Beloved Country (1951), about a minister’s journey through apartheid Johannesburg, is perhaps the earliest example in cinema of consciousness about race and repression. What indication of racism more painful than the fact that the Hungarian (via England) director Zoltán Korda had to get his actors Canada Lee (who died a year after the premiere of the film, aged 45) and a young Sidney Poitier to South Africa through the ruse of a “domestic servant” work permit?

There’s a timely tribute to Berlin-born American filmmaker Michael Roemer featuring his documentary and fiction work, including his offbeat and highly enjoyable study of a small time Jewish mobster in The Plot Against Harry (filmed in 1969, unrealised until 20 years later). Thanks to the suggestions of Ronnie Chammah and the Harvard Film Archive’s efforts, we’ll also be screening his seminal work, Nothing but a Man (1964) in which Roemer, a Jewish immigrant himself, evokes “the insidious everyday experience of racism in the USA, now seen through the eyes of a Black man seeking work and a new start in his life.” In addition to the portrait of Eldridge Cleaver, an early leader of the Black Panther Party, in Black Panther (William Klein, 1970), one of the highlights of the year is the glorious Bushman (David Schickele, 1971), about a Nigerian student in late 1960s San Francisco. With a lucid approach to his cultural identity, the leading character moves in America’s white intellectual circles and encounters the more covert face of racism before being deported. After his expulsion, the film dedicates its final 15 minutes – in Godardian style – to report on the actor playing the character who was deported in real life. This is firstrate cinema: bold, sincere and moving from beginning to end.

Sisters of Cinema

This year, the sisters of cinema have a strong presence on both sides of the camera. We would like to draw your attention to an eye-opening retrospective: the tribute to Suso Cecchi d’Amico, lovingly curated by her children. It is a family insight into a professional career comprising contributions to over 120 screenplays that infinitely enriched the golden age of Italian cinema and beyond. As the only female screenwriter in Italian cinema, she was a master of field research, studying ordinary people, and coming up with lines, situations and character sketches that stemmed from the daily realities she persistently observed and turned into words. She showed an immaculate understanding of the different shades of life, its agonies and its joys.

The retrospective on cinematographer and director Elfi Mikesch, presenting five of her directorial efforts, finds, in her own words, tangible visual representation for the dreams that deal with the impossible and the forbidden. Martin Koerber’s selection takes us into her universe of striking images, dealing with “passion, power, love, pain and death.”

Women also turn the camera on women. There’s Antonia: A Portrait of the Woman (1974) by Judy Collins and Jill Godmilow, recalling the life and career of classical music conductor and pianist Antonia Brico. The literal sisters of cinema, Clara and Julia Kuperberg, have turned their camera on Dorothy Arzner in Une pionnière à Hollywood, a new documentary chronicling the amazing story of the great female auteur of classical

Hollywood who brought a handful of innovations to the studio system. Lee Grant, often a brilliant actor, goes behind the camera in Down and Out in America (1986) to study the ruinous impact of Reagan era policies on marginalised people, demonstrating a fierce political commitment that remains relevant to this day. The same commitment existed through the entire career of the Lebanese filmmaker Jocelyne Saab who filmed all the key moments – revolutions, wars, atrocities – of the 20th century Middle East in her candid and brutally frank films. This year’s programme features her classic 1974 film, Les Femmes palestiniennes.

Additionally, there is the cinematic work of the artist and filmmaker Joyce Wieland to discover. She is not the only female director from a painting background. In A Dream Longer Than the Night (Un rêve plus long que la nuit, 1976), the French American sculptor and painter Niki de Saint Phalle uses moving images as a new means of self-expression. Women filmmakers also revisit and deconstruct the work of their male counterparts as Chantal Akerman offers her hypnotising take on Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958) in The Captive (La Captive, 2000), to be shown in a restored version.

Some sisters of cinema had to be brought out of the shadow of neglect and forgetfulness. The section dedicated to Russian divas of silent cinema in Italy, the result of passionate research and precise detective work, is a foray into a world once deemed to be gone forever. This programme on the great female stars of silent days, previously confined to speculative footnotes in books about lost films, is testimony to the incandescent magnetism of Diana Karenne, Helena Makowska, Thaïs Galitsky and Ileana Leonidoff.

Sweet Little Sixteen

Sweet, maybe. But hardly little, the format revolutionised not only filmmaking (educational, industrial, journalistic, experimental, amateur, television) but also film viewing habits and the circulation of film history. It’s the centenary of 16mm, first introduced by Eastman Kodak. This is a charming tribute as many members of a certain generation will have seen their first “projected” films, in schools, churches and community centres on 16mm. Karl Wratschko’s selection, however, is not the type of cinema one might have seen in a mosque or a church, definitely not the trippy world of outsider Etienne O’Leary anyway. To complete the saga of sixteen, the programme presents the 16mm trailers of films now deemed lost, as well as abridged 16mm versions of the feature films originally shot in 35mm. If you feel life is too short, go and watch the 18-minute version of The Raven (1935), starring Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi, in which the terror is more or less intact but the raven itself is missing.

Our Histories of Cinema

In 2020, a still from Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless became our festival poster. In 2022, we screened his sage farewell to life, distilled into an assuredly benign gaze into the camera in the documentary À vendredi, Robinson. Two months after our last edition, he was gone. Therefore, it seemed appropriate to invite you to the first public screening of his cinema lessons at the Concordia University in Montreal, dating back to the late 1970s, in which he offers reflections on filmmaking, economics, war, political commitment, and the media.

We couldn’t help thinking that Il Cinema Ritrovato, in many ways, has been a live version of his most direct film about cinema, Histoire(s) du cinéma, in which the images overlap and superimpose while parallel histories intertwine and affect each other’s meanings in a forensically lyrical spirit. This is what Il Cinema Ritrovato has been trying to do with six screens, two outdoor venues and nearly 450 titles spread across more than 15 strands: living Histoire(s) du cinéma in real time.

Il Cinema Ritrovato is where images and ideas collide. Welcome to our 2023 encounter!